São Paulo (state)

São Paulo (Portuguese pronunciation: [sɐ̃w ˈpawlu](listen) ) is one of the 26 states of the Federative Republic of Brazil and is named after Saint Paul of Tarsus. A major industrial complex, the state has 21.9% of the Brazilian population and is responsible for 33.9%[7] of Brazil's GDP. São Paulo also has the second-highestHuman Development Index (HDI) and GDP per capita, the fourth-lowest infant mortality rate, the third-highest life expectancy, and the third-lowest rate of illiteracy among the federative units of Brazil. São Paulo alone is wealthier than Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia combined.[8] São Paulo is also the world's twenty-eighth-most populous sub-national entity and the most populous sub-national entity in the Americas.

With more than 46 million inhabitants in 2019, São Paulo is the most populous Brazilian state, the most populous national subdivision in the Americas,[2] and the third most populous political unit of South America, surpassed only by the rest of the Brazilian Federation and Colombia. The local population is one of the most diverse in the country and descended mostly from Italians, who began immigrating to the country in the late 19th century;[9] of the Portuguese, who colonized Brazil and installed the first European settlements in the region; indigenous peoples, many distinct ethnic groups; Africans, who were brought from Africa as slaves in the colonial era and migrants from other regions of the country. In addition, Arabs, Germans, Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, and Greeks also are present in the ethnic composition of the local population.

The area that today corresponds to the state territory was already inhabited by indigenous peoples from approximately 12,000 BC. In the early 16th century, the coast of the region was visited by Portuguese and Spanish explorers and navigators. In 1532 Martim Afonso de Sousa would establish the first Portuguese permanent settlement in the Americas[10]—the village of São Vicente, in the Baixada Santista. In the 17th century, the paulistas bandeirantes intensified the exploration of the colony's interior, which eventually expanded the territorial domain of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire in South America. In the 18th century, after the establishment of the Province of São Paulo, the region began to gain political weight. After independence in 1820, São Paulo began to become a major agricultural producer (mainly coffee) in the newly constituted Empire of Brazil, which ultimately created a rich regional rural oligarchy, which would switch on the command of the Brazilian government with Minas Gerais's elites during the early republican period in the 1880s. Under the Vargas Era, the state was one of the first to initiate a process of industrialization and its population became one of the most urban of the federation.

The city of São Paulo, the homonymous state capital, is ranked as the world's 12th largest city and its metropolitan area, with 20 million inhabitants,[2] is the 9th largest in the world and first in the Americas. Regions near the city of São Paulo are also metropolitan areas, such as Campinas, Santos, Sorocaba and São José dos Campos. The total population of these areas coupled with the state capital—the so-called "Expanded Metropolitan Complex of São Paulo"—exceeds 30 million inhabitants, i.e. approximately 75 percent of the population of São Paulo statewide, the first macro-metropolis in the southern hemisphere, joining 65 municipalities that together are home to 12 percent of the Brazilian population.

Contents

History

Early period

In pre-European times, the area that is now São Paulo state was occupied by the Tupi people's nation, who subsisted through hunting and cultivation. The first European to settle in the area was João Ramalho, a Portuguese sailor who may have been shipwrecked around 1510, ten years after the first Portuguese landfall in Brazil. He married the daughter of a local chieftain and became a settler. In 1532, the first colonial expedition, led by Martim Afonso de Sousa of Portugal, landed at São Vicente (near the present-day port at Santos). De Sousa added Ramalho's settlement to his colony.

Early European colonization of Brazil was very limited. Portugal was more interested in Africa and Asia. But with English and French raiding privateer ships just off the coast, the territory had to be protected. Unwilling to shoulder the naval defense burden himself, the Portuguese ruler, King Joao III, divided the coast into "captaincies", or swathes of land, 50 leagues apart. He distributed them among well-connected Portuguese, hoping that each would be self-reliant. The early port and sugar-cultivating settlement of São Vicente was one rare success connected to this policy. In 1548, João III brought Brazil under direct royal control.

Fearing Indian attack, he discouraged development of the territory's vast interior. Some whites headed nonetheless for Piratininga, a plateau near São Vicente, drawn by its navigable rivers and agricultural potential. Borda do Campo, the plateau settlement, became an official town (Santo André da Borda do Campo) in 1553. The history of São Paulo city proper begins with the founding of a Jesuit mission of the Roman Catholic order of clergy on January 25, 1554—the anniversary of Saint Paul's conversion. The station, which is at the heart of the current city, was named São Paulo dos Campos de Piratininga (or just Pateo do Colégio). In 1560, the threat of Indian attack led many to flee from the exposed Santo André da Borda do Campo to the walled fortified Colegio. Two years later, the Colégio was besieged. Though the town survived, fighting took place sporadically for another three decades.

By 1600, the town had about 1,500 citizens and 150 households. Little was produced for export, save a number of agricultural goods. The isolation was to continue for many years, as the development of Brazil centered on the sugar plantations in the north-east.

The city's location, at the mouth of the Tietê-Paranapanema river system (which winds into the interior), made it an ideal base for another activity—enslaving expeditions. The economics were simple. Enslaved manpower for Brazil's northern sugar plantations were in short supply. Enslaved Africans were expensive, so demand for indigenous captives soared. The task was, nonetheless, hard, if not impossible, to achieve.

Expansion

Among those who attempted to enslave the native were explorers of the hinterland called "bandeirantes". From their base in São Paulo, they also combed the interior in search of natural riches. Silver, gold and diamonds were companion pursuits, as well as the exploration of unknown territories. Roman Catholic missionaries sometimes tagged along, as efforts at converting the natives aborigines (Indians) worked hand in hand with Portuguese colonialism.

Despite their atrocities, the wild and hardy bandeirantes are now equally remembered for penetrating Brazil's vast interior. Trading posts established by them became permanent settlements. Interior routes opened up. Though the bandeirantes had no loyalty to the Portuguese crown, they did claim land for the king. Thus, the borders of Brazil were pushed forward to the northwest and the Amazon region and west to the Andes Mountains.

French Emperor Napoleon's invasion of Portugal in 1807 prompted the British with their vast powerful Royal Navy to evacuate King João VI of Portugal, Portugal's prince regent, from the capital Lisbon, across the Atlantic to Rio de Janeiro and Brazil then became the first overseas colony to become the temporary headquarters of the Portuguese Empire. João VI rewarded his hosts with economic reforms that would prove crucial to São Paulo's rise. Brazil's ports—long closed to non-Portuguese ships—were opened up to international trade. Restrictions on domestic manufacturing were waived.

When Napoleon was defeated in 1815, with the end of the Napoleonic Wars, João gave political shape to his territory, which soon became the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. Portugal and Brazil, in other words, were ostensibly co-equals. Returning to Portugal six years later, João left his son, Pedro, to rule as regent and governor.

Empire of Brazil period

Pedro inherited his father's love of Brazil, resisting demands from Lisbon that Brazil should be ruled from Europe once again. Legend has it that in 1822 the regent was riding outside São Paulo when a messenger delivered a missive demanding his return to Europe, and Dom Pedro waved his sword and shouted "Independência ou morte!" (Independence or death).

João had whetted the appetite of Brazilians, who now sought a full break from the monarchy. The ever-restless Paulistas were at the vanguard of the independence movement. The small mother country of Portugal was in no position to resist—on September 7, 1822, Dom Pedro rubber-stamped Brazil's independence. He was crowned emperor shortly afterwards. The emperors ruled an independent Brazil until 1889. Over this time, the growth of liberalism in Europe had a parallel in Brazil. As the Brazilian provinces became more assertive, São Paulo was the scene of a minor (and unsuccessful) liberal revolution in 1842. When independence was declared, the city of São Paulo had just 25,000 people and 4,000 houses, but the next 60 years would see gradual growth. In 1828, the Law School, the pioneer of the city's intellectual tradition, opened. The first newspaper, O Farol Paulistano, appeared in 1827. Municipal developments such as botanical gardens, an opera house and a library, gave the city a cultural boost.

Regardless, São Paulo still faced many hurdles, especially transport. Mule-trains were the main method of transportation, and the road from the plateau down to the port of Santos was famously arduous. In the late 1860s São Paulo got its first railway line, developed by British engineers, to the Port of Santos. Other lines, such as a railway to Campinas, were soon built. This was good timing, because in the 1880s the coffee craze hit in earnest. Brazil, which had been growing it since the mid-18th century, could grow more. The Paraíba valley, which spans the states of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, had suitable soil and climate. São Paulo city, at the western end of the Paraíba valley, was well positioned to channel the coffee to the port of Santos.

Republican era

Meanwhile, the Brazilian monarchy had fallen in 1889. A feudalistic regime, the new republic had friends only among the sugar planters of the Northeast, whose dominance Paulistanos, among others, despised. In 1891, a new federal constitution, which delegated power to the states, was approved. The new coffee elite saw its chance. São Paulo ironed out a power-sharing understanding—known as the "café com leite" (coffee-and-milk) deal—with dairy-rich Minas Gerais, Brazil's other dominant state. Together, they held a virtual lock on federal power. Brazilian politics now became a favourite pastime of the once-rebellious Paulistanos, who sent several presidents to Rio de Janeiro—including Prudente de Morais, Brazil's first civilian president, who took office in 1894.

Plantation labor was needed—this time for coffee, not sugar. Slavery had been fading since the import of enslaved Africans was outlawed in 1850. São Paulo, thanks to such figures as Luiz Gama (a former slave), was a center of abolitionism. In 1888, Brazil abolished slavery (it was the last country in the Americas to do so) and the freed African-Brazilians who had been helping build the nation were then forced to beg for their jobs back, working for food and shelter only because of the failure of the system to integrate them as equal citizens with Euro-Brazilians. In an effort to "bleach the race", as the nation's leaders feared Brazil was becoming a "black country", Spanish, Portuguese and Italian nationals were given incentives to become farm workers in São Paulo. The state government was so eager to bring in European immigrants that it paid for their trips and provided varying levels of subsidy.

By 1893, foreigners made up over 55 percent of São Paulo's population. Fearing oversupply, the government applied the brakes briefly in 1899; then the boom resumed. From 1908, the Japanese arrived in great numbers, many destined for the plantations on fixed-term contracts. By 1920, São Paulo was Brazil's second-largest city; a half-century before, it had been just the tenth-largest. Immigration and migration of Paulistas from other towns as well as Nordestinos and citizens from other states, the coffee industry, and modernization through the manufacturing of textiles, car and airplane parts, as well as food and technological industries, construction, fashion, and services transformed the greater São Paulo area into a thriving megalopolis and one of the world's greatest multiethnic regions.

Early 20th century

Between 1901 and 1910, coffee made up 51 percent of Brazil's total exports, far overshadowing rubber, sugar and cotton. But reliance on coffee made Brazil (and São Paulo in particular) vulnerable to poor harvests and the whims of world markets. The development of plantations in the 1890s, and widespread reliance on credit, took place against fluctuating prices and supply levels, culminating in saturation of the international market around the start of the 20th century. The government's policies of "valorisation "—borrowing money to buy coffee and stockpiling it, in order to have a surplus during bad harvests, and meanwhile taxing coffee exports to pay off loans—seemed feasible in the short term (as did its manipulation of foreign-exchange rates to the advantage of coffee growers). But in the longer term, these actions contributed to oversupply and eventual collapse.

São Paulo's industrial development, from 1889 into the 1940s, was gradual and inward looking. Initially, industry was closely associated with agriculture: cotton plantations led to the growth of textile manufacturing. Coffee planters were among the early industrial investors.

The boom in immigration provided a market for goods, and sectors such as food processing grew. Traditional immigrant families such as the Matarazzo, Diniz, Mofarrej and Maluf became industrialists, entrepreneurs, and leading politicians.

Restrictions on imports forced by world wars and government policies of "import substitution" and trade tariffs, all contributed to industrial growth. By 1945, São Paulo had become the largest industrial center in South America. World War I sent ripples through Brazil. Inflation was rampant. Some 50,000 workers went on strike.

The growing of the urban population grew increasingly resentful of the coffee elite. Disaffected intellectuals expressed their views during a memorable "Week of Modern Art" in 1922. Two years later, a garrison of soldiers staged a revolt (eventually quashed by government troops).

The stand-off was also political: politics had been long monopolised by the Paulista Republican Party, but in 1926 a more left-leaning party rose in opposition. In 1928, the PRP amended São Paulo's state constitution to give it more control over the city. The turbulence was mirrored on Brazil's national scene. With the Great Depression, coffee prices plunged, as did real GDP. Americans, keen investors during the 1920s, backed away.

The opening of the first highway between São Paulo and Rio in 1928 was one of the few bright spots. Into the breach stepped Getúlio Vargas, a southerner veteran in state politics. In Brazil's 1930 presidential elections, he opposed Júlio Prestes, a favorite son of São Paulo. Vargas lost the election, but with backing from Minas Gerais state—São Paulo's former ally and neighbor to the north—he seized power regardless.

Paulista War

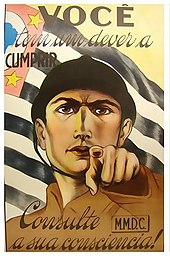

The Constitutionalist Revolution of 1932 or Paulista War is the name given to the uprising of the population of the Brazilian state of São Paulo against the federal government of Vargas. Its main goal was to press the provisional government headed by Getúlio Vargas to enact a new Constitution, since it had revoked the previous one, adopted in 1889. However, as the movement developed and resentment against President Vargas grew deeper, it came to advocate the overthrow of the Federal Government and the secession of São Paulo from the Brazilian federation. But, it is noted that the separatist scenario was used as guerrilla tactics by the Federal Government to turn the population of the rest of the country against the state of São Paulo, broadcasting the alleged separatist notion throughout the country. There is no evidence that the movement's commanders sought separatism.

The uprising started on July 9, 1932, after five protesting students were killed by government troops on May 23, 1932. On the wake of their deaths, a movement called MMDC (from the initials of the names of each of the four students killed, Martins, Miragaia, Dráusio and Camargo) started. A fifth victim, Alvarenga, was also shot that night, but died months later.

Revolutionary troops entrenched in the battlefield. In a few months, the state of São Paulo rebelled against the federal government. Counting on the solidarity of three other powerful states, (Rio Grande do Sul, Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro), the politicians of São Paulo expected a quick war. However, that solidarity was never translated into actual support, and the São Paulo civil war was won by the Federation on October 2, 1932.

In spite of its military defeat, some of the movement's main demands were finally granted by Vargas afterwards: the appointment of a non-military state Governor, the election of a Constituent Assembly and, finally, the enactment of a new Constitution in 1934. However that Constitution was short lived, as in 1937, amidst growing extremism on the left and right wings of the political spectrum, Vargas closed the National Congress and enacted another Constitution, which established an authoritarian regime called Estado Novo.

Late 20th century

Vargas's rule was a study in political turbulence. Elected in 1934, he ruled by dictatorship (albeit a popular one, thanks to his health and social-welfare programmes) from 1937 to 1945—a period dubbed the "Estado Novo". Thrown out by a coup in 1945, he ran for office again in 1950, and was overwhelmingly elected. On the verge of being overthrown from office again, he committed suicide in 1954. Vargas's main legacy was the centralization of power.

The encouragement of industry and diversification of agriculture, not to mention the abolition of subsidies on coffee, finally did away with the dominance of the coffee oligarchies. His replacement, Juscelino Kubitschek, focused on heavy industry. Kubitschek built car factories, steel plants, hydro-power infrastructure and roads. Petrobras, Brazil's oil monolith, was set up in 1953. By 1958, São Paulo state controlled some 55 percent of Brazil's industrial production, up from 17 percent in 1907. Another of Kubitschek's pet projects was the creation of Brasília, which became Brazil's capital in 1960—the year Kubitschek stepped down. The University of São Paulo was founded in 1934; two years after São Paulo's failed uprising. It has established itself as the most prestigious higher learning institution in the country.

With a transitional government from military to civil and a new currency that made stagnant the economy during the mid- to late 1980s, unemployment and crime became rampant. São Paulo, by now the world's third-largest city after Mexico City and Tokyo, was hard-hit. Wealthy Brazilians retreated to suburban highly secured housing complexes such as Alphaville, and favelas, pockets of substandard living slums that lined the periphery, had a tremendous growth. For the first time in history, Brazil experienced large segments of its population immigrating to continents such as North America, Europe, Australia, and East Asia, particularly to Japan.[citation needed]

Geography

São Paulo is one of 27 states of Brazil, located southwest of the Southeast Region. The state area is 248,222.362 km2 (95,839.190 sq mi), most of the north of the Tropic of Capricorn, and the 12th unit of the Brazilian federation in area and the second in the Southeast region, behind only Minas Gerais. The state has a relatively high relief, having 85 percent of its surface between three hundred and nine hundred meters above sea level, 8 percent below three hundred meters and 7 percent over nine hundred meters.[12]

The distance between its north and south end points is 611 km (380 mi), and 923 km (574 mi) between the east–west extremes. The state time zone follows the Brasilia time, which is three hours late in relation to the Greenwich Meridian. It is limited to the states of Minas Gerais to the north and northeast, the Paraná to the south, Rio de Janeiro to the east, Mato Grosso do Sul to the west, and the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast.[13]

The coastline consists of plains below 300 metres (980 ft), that border the Serra do Mar. Located in the Serra da Mantiqueira, Mine Stone, with 2,798 metres (9,180 ft) above sea level, is the highest point the state territory and the fifth in the country.[14]

São Paulo has its territory divided into 21 watersheds,[15] inserted in three river basin districts, the largest of which is the Paraná, which covers much of the state territory. Noteworthy is the Rio Grande, which born in Minas Gerais and join with Paranaiba to form the Parana River, which separates São Paulo from Mato Grosso do Sul.[16]

Two major rivers Paulistas tributaries of the left bank of the Paraná River are the Paranapanema, which is 930 km (580 mi) long and a natural divider between São Paulo and Paraná in most of its course,[17] and the Tiete River, which has a length of 1,136 km (706 mi) and runs through the state territory from southeast to northwest, from its source in Salesópolis, to its mouth in the city of Itapura.[18]

Climate

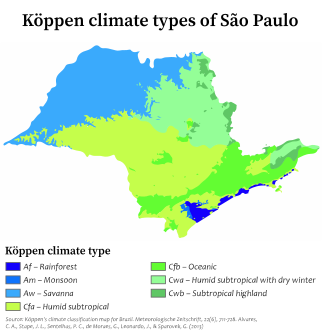

The state territory covers seven distinct climatic types, taking into account the temperature and rainfall. In the mountain areas of the state, there are subtropical climate (Cfa in Köppen climate classification), in areas of high altitude such as the Serra do Mar e Serra da Mantiqueira, having humid, hot summers and average temperatures below 18 °C (64 °F) in the month cooler year; and oceanic (Cfb and Cwb) with regular and well distributed throughout the year and warmer summers rains.[19]

On the coast, the climate is super-humid tropical type, very similar to the prevailing equatorial climate in the Amazon (Af), with rainfall exceeding sixty monthly millimeters in every month of the year, without the existence of a dry season. The tropical climate of altitude (Cwa), predominant in the state territory, specifically in the center of the state, is characterized by a summer rainy season and a dry season in winter, with temperatures above 22 °C (72 °F) in the hottest month of the year. In other areas, there is tropical savanna climate (Aw) with rainfall less than 60 millimetres (2.4 in) in one or more months of the year and warmer, with average temperatures above 18 °C (64 °F) during the year. There are also small areas with characteristics of monsoons (Am).[19]

The occurrence of snow is very rare, but has been recorded in Campos do Jordão and there are also reports that the phenomenon has occurred in several parts of the south of the state, except for the Ribeira Valley.[20] The frosts are common, especially in higher areas with altitude of 800 metres (2,600 ft).[21]

Demographics

According to the IBGE estimates for 2014, there were 44,035,304 people residing in the state. The population density was 177.4 inhabitants per square kilometre (459/sq mi). The last PNAD (National Research for Sample of Domiciles) research revealed the following numbers: 27,612,000 White people (63.1%), 12,842,000 Brown (Multiracial) people (29.3%), 2,810,000 Black people (6.4%), 451,000 Asian people (1%), and 54,000 Amerindian people (0.1%).[23]

People of Italian descent predominate in many towns, including the capital city, where 65 percent of the population has at least one Italian ancestor. The Italians mostly came from Veneto and Campania.[24]

Portuguese and Spanish descendants predominate in most towns. Most of the Portuguese immigrants and settlers came from the Entre-Douro-e-Minho Province in northern Portugal, the Spanish immigrants mostly came from Galicia and Andalusia.

People of African or Mixed background are relatively numerous. São Paulo is also home to the largest Asian population in Brazil, as well to the largest Japanese community outside Japan itself.[25]

There are many people of Levantine descent, mostly Syrian and Lebanese.[26] The majority of Brazilian Jews live in the state, especially in the capital city but there are also communities in Greater São Paulo, Santos, Guarujá, Campinas, Valinhos, Vinhedo, São José dos Campos, Ribeirão Preto, Sorocaba and Itu.

People of more than 70 different nationalities emigrated to Brazil in the past centuries, most of them through the Port of Santos in Santos, São Paulo. Although many of them spread to other areas of Brazil, São Paulo can be considered a true melting-pot. People of German, Hungarian, Lithuanian, Russian, Chinese, Korean, Polish, American, Bolivian, Greek and French background, as well as dozens of other immigrant groups, form sizable groups in the state.

A genetic study, from 2013, showed the overall composition of São Paulo to be: 61.9% European, 25.5% African and 11.6% Native American, respectively.[27]

According to an autosomal DNA genetic study (from 2006), the overall results were: 79 percent of the ancestry was European, 14 percent are of African origin, and 7 percent Native American.[28]

Major cities

Largest municipalities in São Paulo (state)|São Paulo (2011 census by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics)[29] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Mesoregion | Pop. | Rank | Mesoregion | Pop. | ||||

São Paulo Guarulhos | 1 | São Paulo | São Paulo | 11,316,149 | 11 | Santos | Santos | 419,509 | Campinas São Bernardo do Campo |

| 2 | Guarulhos | Guarulhos | 1,233,436 | 12 | São José do Rio Preto | São José do Rio Preto | 412,075 | ||

| 3 | Campinas | Campinas | 1,088,611 | 13 | Mogi das Cruzes | Mogi das Cruzes | 392,195 | ||

| 4 | São Bernardo do Campo | São Paulo | 770,253 | 14 | Diadema | São Paulo | 388,575 | ||

| 5 | Santo André | São Paulo | 678,485 | 15 | Jundiaí | Jundiaí | 373,713 | ||

| 6 | Osasco | Osasco | 667,826 | 16 | Carapicuíba | Osasco | 371,502 | ||

| 7 | São José dos Campos | São José dos Campos | 636,876 | 17 | Piracicaba | Piracicaba | 367,289 | ||

| 8 | Ribeirão Preto | Ribeirão Preto | 612,339 | 18 | Bauru | Bauru | 346,076 | ||

| 9 | Sorocaba | Sorocaba | 593,775 | 19 | São Vicente | Santos | 334,663 | ||

| 10 | Mauá | São Paulo | 421,184 | 20 | Itaquaquecetuba | Mogi das Cruzes | 325,518 |

Religion

According to the 2010 demographic census, of the total population of the state, there were 24 781 288 Roman Catholics (60.06%), 9 937 853 Protestants or evangelicals (24.08%), 1 356 193 spiritists (3.29%), 444 968 Jehovah's Witnesses (1.08%), 153 564 Buddhists (0.37%), 141 553 Umbanda and Candomblecists (0.34%), 81 810 Brazilian Catholic Apostolic Church (0.20%), 70 856 new Eastern religious (0.17%), 65 556 Mormons(0.16%), 51 050, Jewish (0.12%), 31 618 Orthodox Christians (0.08%), 20 375 spiritualists (0.05%), Esoteric 17 827 (0.04%), 14 778 Islamic (0.04%), 4,591 belonging to indigenous traditions (0.01%) and 1,822 Hindus (0.00%). There were still 3 357 682 people without religion (8.14%), 214 332 with indeterminate religion or multiple membership (0.52%), 50 153 did not know (0.12%) and 18 038 did not declare (0.04%).[30][31]

Crime

São Paulo, as well as other states of Brazil, has two types of police forces to carry out public safety in their territory, the Military Police of São Paulo State (PMESP), the largest police in Brazil and the third largest in Latin America, with 138,000 soldiers,[32] and the Civil Police of the State of São Paulo, which exercises judicial police function and is subordinate to the state government.[33]

According to data from the "Map of Violence 2011", published by the Sangari Institute and the Ministry of Justice, the homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants in the state of São Paulo is the lowest in Brazil. The number of homicides in São Paulo fell from 39.7 to 10.1 per 100,000 inhabitants between 1998 and 2014. The state, which occupied the 5th place among the most violent states in the country in 1998, then came to occupy the 27th position in 2016.[34]

Government and politics

The Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB) has formed the government of the state since 1994, and was re-elected in 2018 for four more years. The current governor is João Doria (2019–2023).[35]

Local politicians of note (with party affiliations) include: former President of Brazil (1994–2002) Fernando Henrique Cardoso (PSDB), former president (2002–2010) Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT), José Serra (PSDB), Geraldo Alckmin (PSDB), Mário Covas (PSDB), Antonio Palocci (PT), Eduardo Suplicy (PT), Aloízio Mercadante (PT), Marta Suplicy (MDB), Gilberto Kassab (PSD), and Paulo Maluf (PP). Maluf is a controversial figure in São Paulo City politics, and is frequently accused of corruption. However, many voters used to support him because of his achievements during his governments, which the most well-known was the São Paulo subway system (the first in Brazil) and the João Goulart expressway, also known as Minhocão. Maluf has, however, failed to be elected in the last elections for governor of the state and for mayor of the state capital.

Three of last four Brazilian presidents, Fernando Henrique Cardoso (PSDB), Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT) and Michel Temer (MDB), were politicians from São Paulo, although Cardoso was actually born in the state of Rio de Janeiro, and Lula in Pernambuco. Cardoso and Lula respectively live in the cities of São Paulo and São Bernardo do Campo. The current president, Jair Bolsonaro (PSL), was born in small town of Glicério, in the state northwest, but built his political career in the state of Rio de Janeiro.

According to the Strategist De Leon Petta, São Paulo state is geopolitically responsible to split Brazil in two parts, the federal integrated area and the south non-integrated area. Because of its strong self-determination, São Paulo functions as a backup to the rest of Brazil and as a historical pioneer, creating innovations for the rest of the country to sustain its own demands and needs. If it is a fact that on one side São Paulo functions as a geopolitical buffer, blocking the South from a stronger national cohesion, then the other side is also true—a failed São Paulo would probably wreck all of Brazil. At the same time that São Paulo is an anchor whose administration hinders presidential and federal authority, the state of São Paulo also prevents reckless rulers from freely taking complete control of the country and establishing an excessively centralized government. If by one side this is the reason of the south area has feelings for separation by the other side this prevented major economic and political crisis to spread in the same level across the country.[36]

Economy

In 2009 the service sector was the largest component of GDP at 69%, followed by the industrial sector at 31%. Agriculture represents 2% of GDP. The state produces 34% of Brazilian goods and services. São Paulo (state) exports: vehicles 17%, airplanes and helicopters 12%, food industry 10%, sugar and alcohol fuel 8%, orange juice 5%, telecommunications 4% (2002).

São Paulo state is responsible for approximately a third of Brazilian GDP.[37] The state's GDP (PPP) amounts US$1.221 trillion dollars, making it also the biggest economy of South America and one of the biggest economies in Latin America, second after Mexico. Its economy is based on machinery, the automobile and aviation industries, services, financial companies, commerce, textiles, orange growing, sugar cane and coffee bean production.

São Paulo, one of the largest economic poles in both Latin and South America, has a diversified economy. Some of the largest industries are metal-mechanics, sugar cane, textile and car and aviation manufacturing. Service and financial sectors, as well as the cultivation of oranges, cane sugar and coffee form the basis of an economy which accounts for 34% of Brazil's GDP (equivalent to US$727.053 billion).

The towns of Campinas, Ribeirão Preto, Bauru, São José do Rio Preto, Piracicaba, Jaú, Marilia, Botucatu, Assis, and Ourinhos are important university, engineering, agricultural, zoo-technique, technology, or health sciences centers. The Instituto Butantan in São Paulo is a herpetology serpentary science center that collects snakes and other poisonous animals, as it produces venom antidotes. The Instituto Pasteur produces medical vaccines. The state is also at the vanguard of ethanol production, soybeans, aircraft construction in São José dos Campos, and its rivers have been important in generating electricity through its hydroelectric plants.

Moreover, São Paulo is one of the world's most important sources of beans, rice, oranges and other fruit, coffee, sugar cane, alcohol, flowers and vegetables, maize, cattle, swine, milk, cheese, wine, and oil producers. Textile and manufacturing centers such as Rua José Paulino and 25 de Marco in São Paulo city is a magnet for retail shopping and shipping that attracts customers from the whole country and as far as Cape Verde and Angola in Africa.

In agriculture, it is a giant producer of sugar cane and oranges, and also has large production of coffee, soy, maize, bananas, peanuts, lemons, persimmons, tangerines, cassavas, carrots, potatoes and strawberrys.

In 2019, São Paulo produced 425,617,093 tons of sugar cane.[38] São Paulo production is equivalent to 56.5% of the Brazilian production of 752,895,389 tons, exceeds the production of India (2nd largest world producer of cane) in 2019 (which was 405,416,180 tons) and was equivalent to 21.85% of the world cane production in the same year (1,949,310,108 tons). [39][40][41][42]

In 2019, São Paulo produced 13,256,246 tons of orange.[43] São Paulo production is equivalent to 78% of Brazilian production of 17,073,593 tons, exceeds the production of China (2nd largest orange producer in the world) of 2019 (which was 10,435,719 tons) and was equivalent to 16.84% of world production of orange in the same year (78,699,604 tons). Most of it is destined for the industrialization and export of juice. [44]

In 2017, São Paulo represented 9.8% of the total national production of coffee (third place).[40][45]

The state of São Paulo concentrates more than 90% of the national production of peanuts, and Brazil exports around 30% of the peanuts it produces.[46]

São Paulo is also the largest national producer of banana, with 1 million tons in 2018. The country produced 6.7 million tons this year. Brazil was already the 2nd largest producer of the fruit in the world, currently in 3rd place, losing only to India and Ecuador.[47][48]

The cultivation of soy, on the other hand, is increasing, however, it is not among the largest national producers of this grain. In the 2018/2019 harvest, São Paulo harvested 3 million tons (Brazil produced 120 million).[49]

São Paulo also has a considerable production of maize (corn). In 2019, it produced almost 2 million tons. It is the sixth largest producer of this grain in Brazil. State demand is estimated at 9 million tons, for animal feed, which requires the State of São Paulo to buy corn from other units of the Federation.[50]

In the production of cassava, Brazil produced a total of 17.6 million tons in 2018. São Paulo was the third largest producer in the country, with 1.1 million tons.[51]

In 2018, São Paulo was the largest producer of tangerine in Brazil. About persimmon, São Paulo is the largest producer in the country with 58%. The Southeast is the largest producer of lemon in the country, with 86% of the total obtained in 2018. Only the state of São Paulo produces 79% of the total.[52][53][54]

In 2019, in Brazil, there was a total production area of around 4 thousand hectares of strawberry. São Paulo ranked second in Brazil with 800 hectares, with production concentrated in the municipalities of Piedade, Campinas, Jundiaí, Atibaia and nearby municipalities.[55]

With regard to carrot, Brazil ranked fifth in the world ranking in 2016, with an annual production of around 760 thousand tons. In relation to the exports of this product, Brazil occupies the seventh world position. Minas Gerais and São Paulo are the 2 largest producers in Brazil. In São Paulo, the producing municipalities are Piedade, Ibiúna and Mogi das Cruzes. As for potato, the main national producer is the state of Minas Gerais, with 32% of the total produced in the country. In 2017, Minas Gerais harvested around 1.3 million tons of the product. São Paulo owns 24% of the production.[56][57][58][59]

Regarding the bovine herd, in 2019 São Paulo had approximately 10.3 million head of cattle (6.1 million for beef, 1 million for milk production, 3 million for both). The production of milk this year was 1.78 billion liters. The number of birds to lay eggs was 56.49 million heads. Production of eggs was 1.34 billion dozen. The State of São Paulo is the largest national producer with 29.4%. In the production of poultry for production in São Paulo, there was a production of 690.96 million heads in 2019, equivalent to an offer of 1.57 million tons of chicken. The number of pigs in the state in 2019 is 929.62 thousand heads. Production was 1.46 million head, or 126 thousand tons of pork.[60]

In 2018, when it comes to chickens, the first ranking region was the Southeast, with 38.9% of the total head of the country. A total of 246.9 million chickens were estimated for 2018. The state of São Paulo was responsible for 21.9%. The national production of chicken eggs was 4.4 billion dozen in 2018. The Southeast region was responsible for 43.8% of the total produced. The state of São Paulo was the largest national producer (25.6%). The number of quail was 16.8 million birds. The Southeast is responsible for 64%, highlighting São Paulo (24.6%).[61]

Regarding industry, São Paulo had an industrial GDP of R $378.7 billion in 2017, equivalent to 31.6% of the national industry and employed 2,859,258 workers in the industry. The main industrial sectors are: construction (18.7%), food (12.7%), chemical products (8.4%), industrial services for public services, such as electricity and water (7.9%), and motor vehicles (7.0%). These 5 sectors concentrate 54.7% of the state's industry.[62]

In 2019, Rio de Janeiro was the largest producer of oil and natural gas in Brazil, with 71% of the total volume produced. São Paulo is in second place, with an 11.5% share in total production.[63]

In Brazil, the automotive sector represents about 22% of industrial GDP. ABC Paulista is the first center and largest automobile center in Brazil. When the country's manufacturing was practically restricted to ABC, the State represented 74.8% of Brazilian production in 1990. In 2017, this index decreased to 46.6%, and in 2019, to 40.1%, due to a phenomenon of internalization of vehicle production in Brazil, driven by factors such as unions, which made payroll and labor burdens excessively burdensome, discouraged investment, and favored the search for new cities. The development of ABC cities has also helped curb the appeal, due to rising real estate costs and a higher density of residential areas. São Paulo has factories of GM, Volkswagen, Ford, Honda, Toyota, Hyundai, Mercedes-Benz, Scania and Caoa.[64][65]

In the production of tractors, in 2017, the main manufacturers in Brazil were John Deere, New Holland, Massey Ferguson, Valtra, Case IH and the Brazilian Agrale. They all have factories in the southeast, basically in São Paulo.[66]

In the steel industry, Brazilian crude steel production was 32.2 million tons in 2019. Minas Gerais represented 32.3% of the volume produced in the period, with 10,408 million tons. The other largest steel centers in Brazil in 2019 were: Rio de Janeiro (8,531 million tons), Espírito Santo (6,478 million tons) and São Paulo (2,272 million tons). Some steel manufacturers in São Paulo are COSIPA (owned by Usiminas), Aços Villares and Gerdau, which has factories in Mogi das Cruzes and Pindamonhangaba, which produce special steel, and Araçariguama, which produces long steel for civil construction.[67]

In 2011, Brazil had the sixth largest chemical industry in the world, with net sales of US$157 billion, or 3.1% of world sales. At that time, there were 973 chemical factories for industrial use. They are concentrated in the Southeast Region, mainly in São Paulo. The chemical industry contributed 2.7% to the Brazilian GDP in 2012 and was established as the fourth largest sector in the manufacturing industry. Despite registering one of the largest sales in the sector in the world, the Brazilian chemical industry, in 2012 and 2013, experienced a strong transfer of production abroad, with a drop in national industrial production and an increase in imports. A third of consumption in the country was supplied by imports. 448 products stopped being manufactured in Brazil between 1990 and 2012. This led to the interruption of 1,710 production lines. In 1990, the share of imported products in Brazilian consumption was only 7%, in 2012 it was 30%. The main companies in the sector in Brazil are: Braskem, BASF, Bayer, among others. In 2018, the Brazilian chemical sector was the eighth largest in the world, representing 10% of national industrial GDP and 2.5% of total GDP. In 2020, imports will occupy 43% of the internal demand for chemical products. Since 2008, the average use of capacity in the Brazilian chemical industry has been at a level considered low, ranging from 70 to 83%.[68][69][70]

In Food Industry, in 2019, Brazil was the second largest exporter of processed foods in the world, with a value of U $34.1 billion in exports. The income of the Brazilian food and beverage industry in 2019 was R $699.9 billion, 9.7% of the country's Gross Domestic Product. In 2015, the food and beverage industry in Brazil comprised 34,800 companies (not including bakeries), the vast majority of which were small. These companies employed more than 1,600,000 workers, making the food and beverage industry the largest employer in the manufacturing industry. There are around 570 large companies in Brazil, which concentrate a good part of the total industry income. São Paulo created companies such as: Yoki, Vigor, Minerva Foods, Bauducco, Santa Helena, Marilan, Ceratti, Fugini, Chocolates Pan, Embaré, among others.[71][72][73]

In the Pharmaceutical Industry, most companies in Brazil have been established in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro for a long time. In 2019, the situation was that, due to the tax advantages offered in states like Pernambuco, Goiás and Minas Gerais, companies left RJ and SP and went to these states. In 2017, Brazil was considered the sixth largest pharmaceutical market in the world. Drug sales in pharmacies reached around R $57 billion (US$17.79 billion) in the country. The pharmaceutical market in Brazil had 241 regularized and authorized laboratories for the sale of medicines. Of these, the majority (60%) have national capital. Multinational companies had approximately 52.44% of the market, with 34.75% in commercialized packaging. Brazilian laboratories represent 47.56% of the market in sales and 65.25% in boxes sold. In the distribution of medicine sales by state, São Paulo ranked first: São Paulo's pharmaceutical industry had a turnover of R $53.3 billion, 76.8% of total sales across the country. The companies that benefited the most from the sale of medicines in the country in 2015 were EMS, Hypermarcas (NeoQuímica), Sanofi (Medley), Novartis, Aché, Eurofarma, Takeda, Bayer, Pfizer and GSK.[74][75][76]

In the footwear industry, in 2019 Brazil produced 972 million pairs. Exports were around 10%, reaching almost 125 million pairs. Brazil ranks fourth among world producers, behind China, India and Vietnam, and 11th among the largest exporters. Of the pairs produced, 49% were made of plastic or rubber, 28.8% were made of synthetic laminate, and only 17.7% were made of leather. The largest polo in Brazil is located in Rio Grande do Sul, but São Paulo has important shoe centers, such as the one in the city of Franca, specialized in men's footwear, in the city of Jaú, specialized in women's footwear and in the city of Birigui, specialized in children's footwear. Jaú, Franca and Birigui represent 92% of footwear production in the state of São Paulo. Birigui has 350 companies, which generate around 13 thousand jobs, producing 45.9 million pairs per year. 52% of children's shoes in the country are produced in this city. From Birigui came the majority of the most famous children's shoe factories in the country. Jaú has 150 factories that produce around 130 thousand pairs of cheap women's shoes per day. The footwear sector in Franca has around 550 companies and employs around 20,000 employees. Most of the country's most famous men's shoe factories come from São Paulo. Overall, however, the Brazilian industry has been struggling to compete with Chinese footwear, which has an unbeatable price due to the difference in tax collection from one country to another, in addition to the absence of strong Brazilian labor taxes in China. Brazilian businessmen have had to invest in value-added products, combining quality and design, in order to survive.[77][78][79][80][81]

In the textile industry, Brazil, despite being among the 5 largest producers in the world in 2013, and being representative in the consumption of textiles and clothing, has very little insertion in world trade. In 2015, Brazilian imports ranked 25th (US$5.5 billion). And in exports, it was only 40th in the world ranking. Brazil's share of world textile and clothing trade is only 0.3%, due to the difficulty of competing in price with producers from India and mainly from China. The gross value of production, which includes the consumption of intermediate goods and services, of the Brazilian textile industry corresponded to almost R $40 billion in 2015, 1.6% of the gross value of industrial production in Brazil. São Paulo (37.4%) is the largest producer. The main productive areas of São Paulo are the Metropolitan Region of São Paulo and Campinas.[82]

In Electronics industry, the billing of industries in Brazil reached R $153.0 billion in 2019, about 3% of national GDP. The number of employees in the sector was 234.5 thousand people. Exports were $5.6 billion, and the country's imports were $32.0 billion. Brazil, despite decades-long efforts to rid itself of dependence on technology imports, has yet to reach this level. Imports are concentrated on expensive components such as processors, microcontrollers, memories, magnetic disks, lasers, LEDs and LCDs mounted below. The cables for telecommunications and electricity distribution, cables, optical fibers and connectors are manufactured in the country. Brazil has two large centers for the production of electronic products, located in the Metropolitan Region of Campinas, in the State of São Paulo, and in the Free Trade Zone of Manaus, in the State of Amazonas. There are large, internationally renowned technology companies as well as part of the industries that participate in its supply chain. The country also has other smaller centers, such as the municipalities of São José dos Campos and São Carlos, in the state of São Paulo. In Campinas there are industrial units of groups such as General Electric, Samsung, HP and Foxconn, a manufacturer of Apple and Dell products. São José dos Campos, focuses on the aviation industry. This is where the headquarters of Embraer is located, a Brazilian company that is the third largest aircraft manufacturer in the world, after Boeing and Airbus. In the production of cell phones and other electronic products, Samsung produces in Campinas; LG produces in Taubaté; Flextronics, which produces Motorola cell phones, produces in Jaguariúna; and Semp-TCL produces in Cajamar.[83][84][85]

In the household appliances industry, sales were 12.9 million units in 2017. The sector had its peak in sales in 2012, with 18.9 million units. The brands that sold the most were Brastemp, Electrolux, Consul and Philips. Brastemp is originally from São Bernardo do Campo. São Paulo was also the place where Metalfrio was founded.[86]

Several famous multinationals have factories in São Paulo, such as Coca-Cola, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Ambev, Procter & Gamble and Unilever.

Tourism

A significant portion of the state economy is tourism. Besides being a financial center, the state also offers a huge variety of tourist destinations:

São Paulo, the state capital city is the center of business tourism in Brazil, which gives the city about 45,000 events per year. São Paulo also has the largest hotel network in Brazil. Because of real estate speculation in the mid-1990s, nowadays there is an excess supply in the number of vacancies. The city also has demand in gastronomic culinary tourism after receiving the title of the "World Capital of Gastronomy. Cultural tourism is also highlighted given the amount of museums, theaters and events like the Biennale and the Biennale of Arts of the Book.

The coast of São Paulo state along the South Atlantic Ocean has 622 km of beaches of all kinds and sizes. Among the cities that receive the most tourists in the summer are Santos, Praia Grande, Ubatuba, São Sebastião, among others.

In the interior, it is possible to find resorts, rural tourism, eco-municipalities with a European- like climate, waterfalls, caves, rivers, mountains, spas, parks, historical buildings from the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, and Jesuit / Roman Catholic church architecture archaeological sites such as the Alto Ribeira Tourist State Park (PETAR).

Those looking for intense entertainment can browse the Hopi Hari, a major theme park in Brazil, in the Metropolitan Region of Campinas; the complex also includes a hotel and the water park Wet 'n Wild. Also you can find the Parque Aquático Thermas dos Laranjais, which is the most visited water park in Latin America and the fifth in the world, located in Olímpia, a municipality in the northern part of the state. In terms of ecotourism, Sprout Juquitiba has a fine infrastructure. In winter, the city of Campos do Jordão emerges as the main tourist reference state, with the Winter Festival and several other attractions in an environment where the temperature can drop down below 0 (zero) degrees (Celsius).

Education and science

With 15.027 primary schools, 12.539 pre-school units, 5.639 secondary schools and more than 578 universities,[87] the state's education network is the largest in the country.[88]

The HDI education factor in the state in 2005 reached the mark of 0.921 - a very high level, in accordance with the standards of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

São Paulo is also the largest research and development center in Brazil, responsible for 52% of Brazilian scientific production and 0.7% of world production in the period between the 1998 and 2002. In addition to many universities, São Paulo also has important research institutes such as the Institute of Technological Research (IPT), the Nuclear and Energy Research Institute (IPEN), the Butantan Institute, the Biological Institute, the Pasteur Institute, the Institute of Tropical Medicine of São Paulo (IMTSP), the Forestry Institute, the National Institute of Space Research (INPE), the National Synchrotron Light Laboratory (LNS) and the Agronomic Institute of Campinas (IAC).

Educational institutions

- Instituto de Pesquisas Energéticas e Nucleares (IPEN) (Nuclear and Energy Research Institute, Public);

- Instituto Tecnológico da Aeronáutica (ITA) (Air Force Technological Institute, Public);

- Universidade de São Paulo (USP) (University of São Paulo, Public);

- Universidade Federal de São Paulo (Unifesp) (Federal University of São Paulo, Public);

- Universidade Estadual Paulista (Unesp) (São Paulo State University, Public);

- Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp) (University of Campinas, Public);

- Universidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCar) (Federal University of São Carlos, Public);

- Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de São Paulo (IFSP) (São Paulo Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology, Public);

- Instituto Mauá de Tecnologia (Mauá) (Mauá Institute of Technology, Private);

- Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC-SP) (Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo, Private);

- Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie (Mackenzie) (Mackenzie Presbyterian University, Private);

- Universidade de Sorocaba (UNISO) (University of Sorocaba, Private)

- Fundação Getúlio Vargas (FGV) (Getúlio Vargas Foundation, Private);

- Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas (Pontifical Catholic University of Campinas, Private);

- Universidade Federal do ABC (UFABC) (Federal University of ABC, Public);

- Faculdade de Medicina de Marília (FAMEMA) (Marília Faculty of Medicine, Public);

- Faculdade de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto (FAMERP) (São José do Rio Preto Faculty of Medicine, Public);

- Universidade Metodista de São Paulo (UMESP) (Methodist University of São Paulo, Private);

- Faculdade de Teologia Metodista Livre (FTML) (Free Methodist College, Private);

- Faculdade de Tecnologia do Estado de São Paulo (FATEC) (São Paulo State Technological College, Public);

- Universidade de Ribeirão Preto (UNAERP) (Ribeirão Preto, Private);

- Universidade de Marília (UNIMAR) (Marília, Private);

- Universidade Paulista (UNIP) (Private)

Infrastructure

Transport

Every day nearly 100,000 people pass through São Paulo-Guarulhos International Airport (IATA: GRU, ICAO: SBGR), which connects Brazil to 28 countries. There are 370 companies established there, generating 53,000 jobs. The original airport's two terminals are designed to handle 20.5 million passengers a year, but the recently opened third terminal expanded the capacity for 42 million users.[89]

São Paulo International Airport is also one of the main air cargo hubs in Brazil. The roughly 100 cargo flights a day carry everything from fruits grown in the São Francisco Valley to medications. The airport's cargo terminal is South America's largest and stands behind only Mexico City's in all of Latin America. In 2013, over 343 thousand metric tons of freight passed through the container terminal.[90]

Congonhas-São Paulo Airport or just Congonhas Airport (IATA: CGH, ICAO: SBSP) is one of São Paulo's three commercial airports, situated 8 kilometres (5 miles) from the city downtown at Washington Luís Avenue, in the Campo Belo district. It is owned by the City of São Paulo and managed by Infraero. In 2013, it was the busiest airport in Brazil in terms of aircraft movements and the second busiest in terms of passengers, handling 209,555 aircraft movements and 17,119,530 passengers.[91]

Located 14 kilometers from downtown Campinas and 99 kilometers from the city of São Paulo, Viracopos-Campinas International Airport (IATA: VCP, ICAO: SBKP) can be reached by three highways: Santos Dumont, Bandeirantes and Anhanguera. The city of Campinas is one of Brazil's leaders in technology. Besides excellent highway connections, it is the location of major universities and many high-tech companies. Because of this, the airport is one of Infraero's highest investment priorities. The old "landing field" as it was called has become one of the main connection points in Latin America.

The air cargo import/export terminal of Campinas has an area of over 81,000 square meters. The airport began to concentrate in the international air cargo sector in the 1990s and today this is the airports leading source of revenue. Since 1995, Infraero has been investing to implement the first phase of the airport's master plan, making major improvements to the cargo and passenger terminals. The first phase was completed in the first half of 2004, when the airport received new departure and arrival lounges, public areas and commercial concessions. In 2012, the airport received a new terminal, it has since been privatized.

In rail transport, the state has more than 5,000 km (3,100 mi) of railways, which comes from the banks of the Parana River on the border of São Paulo and Mato Grosso do Sul, to the Port of Santos, on the Atlantic coast, for the carriage of goods. The first of such urban transit systems in Brazil and South America, it began operations in 1974. It consists of four color-coded lines: Line 1-Blue, Line 2-Green, Line 3-Red and Line 5-Lilac; Line 4-Yellow started to work in May 2010, and will be completed only in 2016.[92]

The metro system carries 2.8 million passengers a day. Metro itself is far from covering the entire urban area in the city of São Paulo. Another company, Companhia Paulista de Trens Metropolitanos (CPTM), ["São Paulo Metropolitan Train Company"] works along with the metro system and runs additional commuter railways converted into light rail service lines, which total six lines (numbers 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12), 261 km long, serving 89 stations. Metro and CPTM are integrated through various stations. Metro and CPTM both operate as state-owned companies, and have received awards in the recent past as one of the cleanest systems in the world by ISO9001. The São Paulo metro transports three million people by day. A regional rail network is also proposed.

The highway system of São Paulo is the largest state system of the Brazilian Highway System, surpassing the 35,000 km (22,000 mi). It is an interconnected network, divided into three levels: municipal (12,000 km (7,500 mi)); state (22,000 km (14,000 mi)); and federal (1,050 km (650 mi)). More than 90% of São Paulo population is about 5 km (3.1 mi) from a paved road.[93]

São Paulo has the largest number of highways of Latin America and, according to a survey by the Confederação Nacional do Transporte (National Transport Confederation), the road system of the state is the best in Brazil, with 59.4% of its roads classified as "excellent".[94] The survey also found that of the 10 best Brazilian highways, nine are in São Paulo.[94]

The São Paulo highway system, however, is heavily criticized for the high cost imposed on its users. The state of São Paulo concentrates more than half of the toll roads in Brazil and a new toll plaza is created every 40 days average. According to a report of the Folha de S. Paulo, the cost of tolls to travel the coastal path of 4,500 km (2,800 mi) of the federal highway BR-101, which connect Rio Grande do Norte to Rio Grande do Sul, is cheaper than to go through the 313 km (194 mi) of highways separating the municipalities of São Paulo and Ribeirão Preto.[95] The prices charged by private concessionaires who run the system are frequent targets of complaints from drivers.[96]

Ports

In maritime transport, the state of São Paulo has two major ports: the Port of Santos, located in municipality of Santos and occupies the 39th position in the world by containerized cargo; and the Port of São Sebastião, located in São Sebastião (San Sebastian) municipality.[97]

Water

Culture

São Paulo state is a cosmopolitan region, a land influenced by its encounter with different traditions beginning with the Tupi-Guarani Native American nation, the intrusion of Iberian and other European elements and the traffic of enslaved Africans. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, European, Asian, and Middle-Eastern immigrants also made their way there. Earlier, the land had been the starting point of the bandeirantes expeditions, which sought to enslave the Natives of the hinterlands and explore their mineral wealth. Hence, São Paulo influenced most of Western Brazil, as well as the states of Minas Gerais, its neighbor north of it, and Paraná, which was originally part of the old São Paulo province.

A very distinctive character in the culture of São Paulo state is the Caipira tradition, a mixture of Luso-Native-Brazilian and immigrant elements, mainly southern Italian, which influenced its dialect, somewhat different from the Portuguese language spoken in São Paulo city, although the latter is also heavily Italianized. The caipira culture is strong in countryside cities, although centers like Piracicaba, São Carlos, São José do Rio Preto, Araraquara, Ribeirão Preto, Barretos, Campinas, Marilia, Assis, Presidente Prudente, Jaú and Bauru also have a strong retroflex R style of pronunciation and unusual usage of words. It seems that the influence is actually from the Calabrian or Sicilian Italian dialect though, and many of the words peculiar to the region are actually archaic Portuguese forms. Native languages might[dubious – discuss] also have stressed the more nasal sounds of words ending in /m/ or /n/, which is also a feature of other dialects in Brazil.[citation needed]

Cuisine

Caipira food typically includes fried or barbecued beef steaks; fried eggs; couve (collard green); taioba (cabbage); manioc (corn flour); farofa (stuffing); frango Caipira (freshly baked or pan-seared chicken); frango a Passarinho (fried chicken pieces of chicken); fried breaded sardine or fish fillet; and pork chops or baked pork with lettuce or cabbage and tomato, seasoned with garlic, lemon, and onions. Bean stew with carne seca (dried charque beef), toicinho (bacon) and white rice is always the staple, but macarronada (spaghetti) is always present on Sunday luncheons, and fried sausages are often eaten daily. Mildly spiced legumes, as well as zucchini and other types of squash, are often prepared as a stew with or without meat, and sometimes with quiabo (ocra) and abobora or butternut squash are a favorite dessert, as are sweetened sidra, canjica (white corn kernels cooked in milk, coconut, and condensed milk and peanut bits). Pudim de leite, or milk custard, pave' (mounted cookies in rich condensed and heavy cream sauce) and manjar (white flan) are other mouth-watering treats. If none of these desserts are present, countryside meals will rarely leave out citrics such as oranges and mexericas, bananas, caquis or abacaxi (pineapple). Home-made loaves or regular bakery fresh rolls with butter or corn meal or orange cakes are served with coffee and milk or mate tea in the afternoon before dinner or before bed. Pastries like chicken coxinha fried dumplings and risolis, and the Mediterranean or Syrian-Lebanese kibe and open sfihas are often served in birthday and wedding parties followed by a glazed cake, guarana' and other sodas, champagne, caipirinha sugar-cane liquor or beer. Chopp or draft beer is a must in weddings celebrations.

Fine arts

Another distinctive character in the state of São Paulo is the so-called "Brazilian erudite culture". São Paulo was the home of the Brazilian Week of Modern Art (Semana da Arte Moderna), organized mostly by poets and artists from São Paulo, like Mário de Andrade, Oswald de Andrade, Menotti del Picchia, Tarsila do Amaral and Anita Malfatti, Victor Brecheret and Lasar Segall. São Paulo was also the birthplace of Brazilian classical composers, like Carlos Gomes (the most famous Brazilian opera composer), Elias Álvares Lobo and Camargo Guarnieri. OSESP, the São Paulo state orchestra is known internationally and it has had both national and international directors.

Museums

São Paulo has some of the most impressive museums in the country, such as the Museu Paulista do Ipiranga, which honors the site of the independence of Brazil and has numerous Native American artifacts, funeral urns and other historic objects, besides the monument resting place of Dom Pedro, Brazil's first emperor and his wife. The Museu de Arte de São Paulo or MASP on Avenida Paulista is the most important Latin American collection of European paintings, and the Pinacoteca do Estado on Avenida Tiradentes exhibits paintings and sculptures. The Museu de Arte Sacra on the same avenue features national Barroc art and an Italian nativity scene, besides having in the chapel next door, the tomb of Frei Galvão, the first Brazilian saint. Across from Pinacoteca is the Luz station built in Britain and assembled in Brazil with the innovating Museu da Língua Portuguesa, the first interactive language museum in the world. Ibirapuera Park features Museu do Presepio or Creche museum, AfroBrasil, the African-Brazilian museum, and the Bienal book and art fair site conducted every two years. The city of São Carlos in the center of the state has the Museu do Avião, an open airplane museum.

Sports

Football is the most popular sport in the state. The biggest clubs from the state are Corinthians, Palmeiras, São Paulo, Santos, Ponte Preta, Guarani, Portuguesa, XV de Piracicaba. Other sports like Basketball and Volleyball are also quite popular. In basketball, famous Brazilian players such as Hortência Marcari, "Magic" Paula and Janeth Arcain are from São Paulo. Many of the internationally recognized racing drivers, like Emerson Fittipaldi, Ayrton Senna, Rubens Barrichello, Hélio Castroneves and Felipe Massa are also from São Paulo.

São Paulo hosted the opening game in the 2014 FIFA World Cup, that took place in Brazil.

Corrida de São Silvestre

The São Silvestre Race takes place every New Year's Eve in São Paulo. It was first held in 1925, when the competitors ran about 8,000 metres across the streets. Since then, the distance raced has varied, and it is now fixed at 15 km. Registration takes place from 1 October, with the maximum number of entrants limited to 15,000. In 1989, The São Silvestre Race became two races, the masculine and the feminine competition. There is also a children's race called São Silvestrinha.

Brazilian Grand Prix

The Brazilian Grand Prix (Portuguese: Grande Prêmio do Brasil) is a Formula One championship race which occurs at the Autódromo José Carlos Pace in Interlagos. In 2006 the Grand Prix was the final round of the FIA Formula 1 World Championship. The Spanish driver Fernando Alonso won the 2006 drivers championship at this circuit by coming second in the race. The race was won by the young Brazilian driver Felipe Massa, driving for the Scuderia Ferrari team.

See also

- List of municipalities in São Paulo by HDI

- List of municipalities in the state of São Paulo by population

- List of people from São Paulo

- History of the State of São Paulo

- History of the City of São Paulo

References

- "Panorama - São Paulo". IBGE. July 1, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- "Estimativas da população residente no Brasil e Unidades da Federação com data de referência em 1º de julho de 2014"(PDF) . IBGE. October 31, 2014. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2017-05-25. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- "IBGE Projeção da população". www.ibge.gov.br. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- Seade, Fundação. "Fundação SEADE". Fundação Seade (in Portuguese). Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "PIB TRIMESTRAL DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO"(PDF) . Seade. Sao Paulo State Government. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "Radar IDHM: evolução do IDHM e de seus índices componentes no período de 2012 a 2017"(PDF) (in Portuguese). PNUD Brasil. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "São Paulo State". UNICAMP in English.

- "Forget the nation-state: cities will transform the way we conduct foreign affairs". World Economic Forum. 4 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- "Essa Gente Paulista – Italianos" (in Portuguese). Sao Paulo's State Government. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- Rachel Lawrence: 2010, p. 183

- IGBE

- "GEOGRAFIA DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO"(PDF) (in Portuguese). Virtual Library of the State of São Paulo. March 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- "CARACTERIZAÇÃO DO TERRITÓRIO: DIVISÃO, POSIÇÃO E EXTENSÃO". Anuário Estatístico do Estado de São Paulo 2003 (in Portuguese). Fundação Seade. 2003. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- Pereira, Chico (6 July 2013). "Área da Pedra da Mina vai virar patrimônio natural de SP" (in Portuguese). Portal O Vale. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- "Comitês das bacias hidrográficas do estado de São Paulo" (in Portuguese). Portal CBH. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- "RIO PARANÁ" (in Portuguese). Portal Itaipu. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- "Rio Paranapanema da nascente à foz" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Denis (23 September 2010). "Rio Tietê faz aniversário!" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- MIRANDA, Marina J. de.; et al. "A CLASSIFICAÇÃO CLIMÁTICA DE KOEPPEN PARA O ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO" (in Portuguese). Centro de Pesquisas Meteorológicas e Aplicadas à Agricultura (CEPAGRI). Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- "26 de junho de 1918 – Registro de Neve em São Paulo?" (in Portuguese). Jornal do Comércio. 26 June 1918. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- "Geadas" (in Portuguese). Prefeitura de Maricá/RJ. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- "Tabela 2094: População residente por cor ou raça e religião". sidra.ibge.gov.br. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- "Sistema IBGE de Recuperação Automática (SIDRA)". IBGE. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- "Fundaçãolo Lorenzato". Archived from the original on 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- "6 Biggest Japanese Communities Outside Japan". Japan Talk. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- "The Syrian-Lebanese diaspora in São Paulo, Brazil"(PDF) .

- Saloum De Neves Manta, Fernanda; Pereira, Rui; Vianna, Romulo; Rodolfo Beuttenmüller De Araújo, Alfredo; Leite Góes Gitaí, Daniel; Aparecida Da Silva, Dayse; De Vargas Wolfgramm, Eldamária; Da Mota Pontes, Isabel; Ivan Aguiar, José; Ozório Moraes, Milton; Fagundes De Carvalho, Elizeu; Gusmão, Leonor (2013-09-20). "Revisiting the Genetic Ancestry of Brazilians Using Autosomal AIM-Indels". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e75145. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...875145S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075145. PMC3779230 . PMID24073242 .

- Ferreira, Luzitano Brandão; Mendes, Celso Teixeira; Wiezel, Cláudia Emília Vieira; Luizon, Marcelo Rizzatti; Simões, Aguinaldo Luiz (2006-08-17). "Genomic ancestry of a sample population from the state of São Paulo, Brazil". American Journal of Human Biology. 18 (5): 702–705. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20474. PMID16917899 . S2CID10103856 .

- "Estimativas da população residente nos municípios brasileiros com data de referência em 1º de julho de 2011" [Estimates of the Resident Population of Brazilian Municipalities as of July 1, 2011] (in Portuguese). Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. 30 August 2011. Archived from the original(PDF) on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- «Censo 2010». IBGE

- «Análise dos Resultados/IBGE Censo Demográfico 2010: Características gerais da população, religião e pessoas com deficiência» (PDF)

- "Polícia Militar do Estado de São Paulo - Institucional". Archived from the original on 2009-01-14. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- "CONSTITUIÇÃO DA REPÚBLICA FEDERATIVA DO BRASIL DE 1988". www.planalto.gov.br.

- Waiselfisz, Julio Jacobo (2016). "Lista de estados e capitais mais violentos". G1. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- "João Doria, do PSDB, é eleito governador de São Paulo". G1 (in Portuguese). 28 October 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Costa, De Leon Petta Gomes da. São Paulo: Brazil’s Geopolitical Anchor of Resistance. In Towards New Political Geography, 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2018. https://www.pdf-archive.com/2018/01/23/towards-new-political-geography-chapter-7/towards-new-political-geography-chapter-7.pdf

- Regional Accounts 2012, Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), 2013

- Sugar Cane Result 2019 Brazil Table 1612

- FAO production of world agriculture in 2019

- IBGE prevê safra recorde de grãos em 2020

- Coagro espera a melhor safra da cana-de-açúcar dos últimos quatro anos

- ACOMPANHAMENTO DA SAFRA BRASILEIRA DE CANA DE AÇÚCAR MAIO 2019

- Brazilian orange production in 2019

- FAO production of world agriculture in 2019

- A Reivenção da cafeicultura no Paraná

- Estudo mapeia áreas de produção de amendoim do Brasil para prevenir doença do carvão

- Produção brasileira de banana em 2018

- Custo de produção de banana no sudeste paraense

- Confira como está a colheita da soja em cada estado do país

- Estimativa de Oferta e Demanda de Milho no Estado de São Paulo em 2019

- Produção brasileira de mandioca em 2018

- Produção brasileira de tangerina em 2018

- Caqui – Panorama nacional da produção

- Produção brasileira de limão em 2018

- Qual o panorama da produção de morango no Brasil?

- CENOURA:Produção, mercado e preços

- É batata

- Produtores de batata vivem realidades distintas em Minas Gerais

- Aumento da demanda elevará a colheita de batata em Minas

- Estimativa da Produção Animal no Estado de São Paulo para 2019

- As cidades brasileiras com o maior número de aves

- São Paulo Industry Profile

- Rio aumenta sua participação na produção nacional de petróleo e gás

- Setor Automotivo

- O novo mapa das montadoras

- Produção de tratores no Brasil

- Minas Gerais produz 32,3% do aço nacional em 2019

- Indústria Química no Brasil

- Estudo de 2018

- Produção nacional da indústria de químicos cai 5,7% em 2019, diz Abiquim

- Faturamento da indústria de alimentos cresceu 6,7% em 2019

- "Indústria de alimentos e bebidas faturou R$ 699,9 bi em 2019". 18 February 2020.

- A indústria de alimentos e bebidas na sociedade brasileira atual

- Rio de Janeiro: por que a indústria farmacêutica não o quer?

- Saiba como está a competição no mercado farmacêutico brasileiro

- Roche investe R$ 300 milhões na fábrica do Rio de Janeiro

- Produção de calçados deve crescer 3% em 2019

- Abicalçados apresenta Relatório Setorial 2019

- Exportação de Calçados: Saiba mais

- Saiba quais são os principais polos calçadistas do Brasil

- Industrias calcadistas em Franca SP registram queda de 40% nas vagas de trabalho em 6 anos

- Industria Textil no Brasil

- Fabricante da Motorola mantém operação reduzida por conta de coronavírus e reveza férias coletivas

- Desempenho do Setor - DADOS ATUALIZADOS EM ABRIL DE 2020

- A indústria eletroeletrônica do Brasil – Levantamento de dados

- Um setor em recuperação

- "Universidades em São Paulo". Seruniversitario.com.br. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- "Ensino - matrículas, docentes e rede escolar 2009". IBGE. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- "New terminal in Guarulhos increases the airport's capacity to 42 million passengers per year". Portal da Copa. May 21, 2014.

- "Resumo de movimentação aeroportuária - GRU Airport"(PDF) .

- "Airport Statistics for 2013"(PDF) .

- "Metrô terá primeira estação fora de SP só em 2016" (in Portuguese). O Estado de S. Paulo. May 11, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- "Infraestrutura Rodoviária" (in Portuguese). Government of the State of São Paulo. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- http://www.der.sp.gov.br/institucional/todasnoticias.aspx?ID_Noticias=66

- Alencar, Izidoro (22 December 2009). "Pedágio para cruzar o país pela BR-101 é menor que no Estado de SP" (in Portuguese). Folha de S.Paulo. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- "Estado de São Paulo ganha um pedágio a cada 40 dias – São Paulo – R7" (in Portuguese). r7.com. 5 July 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- "São Paulo" (in Portuguese). 2010. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

Bibliography

- Lawrence, Rachel (January 2010). Dar, Alyse (ed.). Brazil (Seventh ed.). Apa Publications GmbH & Co. / Discovery Channel. pp. 183–204.

External links

Definitions from Wiktionary

Media from Commons

News from Wikinews

Quotations from Wikiquote

Texts from Wikisource

Textbooks from Wikibooks

Travel guides from Wikivoyage

Resources from Wikiversity

- Official website(in Portuguese)

- State Assembly(in Portuguese)

- State Judiciary(in Portuguese)

Geographic data related to São Paulo (state) at OpenStreetMap