Lion Rock

Lion Rock, or less formally Lion Rock Hill, is a mountain in Hong Kong. It is located in Sha Tin District,[1] between Kowloon Tong of Kowloon and Tai Wai of the New Territories, and is 495 metres (1,624 ft) high.[2] The peak consists of granite covered sparsely by shrubs. The Kowloon granite, which includes Lion Rock, is estimated to be around 140 million years old.[3]

Lion Rock is noted for its shape.[4] Its resemblance to a crouching lion is most striking from the Choi Hung and San Po Kong areas in East Kowloon. A trail winds its way up the forested hillside to the top, culminating atop the "lion's head". The trail can be followed across the profile of the lion, eventually linking up with the MacLehose Trail. The rock provides a view of the city and Hong Kong Island in the distance. The entire mountain is located within Lion Rock Country Park, south of Hung Mui Kuk, Tai Wai and is made passable by vehicles by Lion Rock Tunnel, which connects Kowloon Tong and Tai Wai.

Lion Rock is near another famous rock structure, the Amah Rock. A road in Kowloon City is named Lion Rock Road (獅子石道).

Contents

Cultural references

After World War II and Communists' victory in the Chinese Civil War, many people who fled to Hong Kong from Mainland China lived in squatters in Kowloon, where the Lion Rock is clearly visible. The lives of the era, during which Hong Kong was rebuilt from poverty, was depicted by the RTHK in the 1974 TV series Below the Lion Rock. The TV series featured some of the early work of now-famous film directors such as Ann Hui. Its theme song "Below the Lion Rock", sung by Cantopop star Roman Tam, is considered to represent the spirit of the Hong Kong people. The name of the series and its eponymous theme song has since been connected to the "Lion Rock Spirit" (Chinese: 獅子山下精神),[5][6] used to refer to Hong Kong as a whole.

The second version of the government-sponsored Brand Hong Kong contains a silhouette of the Lion Rock. According to the brand, the Lion Rock represents "the Hong Kong people's 'can-do' spirit".[7]

A banner that reads in Chinese “我要真普選” (I want real universal suffrage) was hung up near the head of the 'Lion' on 23 October 2014 to show support for 2014 Hong Kong protests.[7][8] The banner was removed by the government on the next day.[9]

- The Lion Rock Institute is a public policy think tank advocating free market solutions for Hong Kong's policy challenges.

- Gavin Young wrote the history of Cathay Pacific Airways in a book entitled Beyond Lion Rock (1988).

- The reggae band Culture has a song entitled 'Lion Rock'.

- Famed British mountaineer Sir Chris Bonington calls Lion Rock his personal favourite climb in Hong Kong.[10]

History

When the ban on human settlement of coastal areas of the Great Clearance was lifted in 1668, the coastal defense was reinforced. Twenty-one fortified mounds, each manned with an army unit, were created along the border of Xin'an County, and at least five of them were located in present-day Hong Kong. 1) The Tuen Mun Mound, believed to have been built on Castle Peak or Kau Keng Shan, was manned by 50 soldiers. 2) The Kowloon Mound on Lion Rock and 3) the Tai Po Tau Mound northwest of Tai Po Old Market had each 30 soldiers. 4) The Ma Tseuk Leng Mound stood between present-day Sha Tau Kok and Fan Ling and was manned by 50 men. 5) The fifth one at Fat Tong Mun, probably on today's Tin Ha Shan Peninsula, was an observation post manned by 10 soldiers. In 1682, these forces were re-organized and manned by detachments from the Green Standard Army with reduced strength.[11][12]

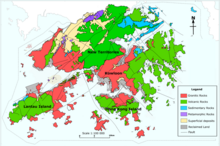

Geology

The many mountains in the Kowloon area, which include Lion Rock, are formed by Granitic rocks. This is in contrast to some of the highest mountains in Hong Kong that are formed by much younger Volcanic rocks, such as Tai Mo Shan (957 m, the highest mountain).[13]

Geography

To the north of Lion Rock are the new towns of Tai Wai and Sha Tin. To the west is Beacon Hill (457 metres (1,499 ft)), which has a civil aviation tower on its summit. To the south is the Wong Tai Sin area, while to the west, there is another mountain called Temple Hill (488 metres (1,601 ft)).

Hiking

According to the Hong Kong Government, the Lion Rock summit is one of 16 "high risk locations" for hikers in Hong Kong owing to its level of difficulty.[14][15]

A few parts of the trail are rocky and have no barrier fencing, so hikers are exposed to falls off steep cliffs.[16] Numerous signs are placed by the Government throughout the trail to warn hikers of this danger. It is not advisable to take selfies close to the edge of the cliffs on foggy or wet days,[17] or take shortcuts to the summit, as hikers have died needlessly trying to do so.[18][19][20]

A number of deaths have occurred on this trail.[18][19][20][21][22] Casual tourists who are not properly prepared should not attempt this hike.

Hiking Fatalities

- On December 20, 1982, a 14-year-old British boy fell off a 30-meter cliff from the lion's head and died.[23]

- On April 1, 2007, a 48-year-old woman lost her way while climbing Lion Rock with her companions, fell off a 100m-cliff and died.[24]

- On September 10, 2008, a 26-year-old man fell off a 40-meter cliff and died while hiking on Lion Rock.[25]

- In November 2011, a 73-year-old hiker fell off a cliff at the top of Lion Rock and died.[26]

- On March 12, 2016, when a 22-year-old man climbed to the top of Lion Rock alone to take pictures, he stumbled and fell 400 meters off a cliff and died.[27]

- On October 5, 2019, a woman was found dead 20 meters under the western cliff of Lion Rock.[28]

- On January 28, 2020, a man fell off a cliff from Lion Rock and was found on a slope 200 meters under the Lion’s head.[29]

- On November 21, 2020, a 56-year-old woman accidentally fell 30 meters off a cliff while climbing on a treacherous mountainside trail south of Lion’s Tail. She was pronounced dead after a 4-hour rescue operation. [30]

Environment

- The Lion Rock trail, unlike tourist-friendly Victoria Peak, is a country park trail and has no street lights, roads or cable cars. It is completely dark by the evening. Some parts of the trail can be rocky, so when hikers go up or down the trail in total darkness, one should have a strong flashlight and backup batteries.

- Hikers who go up or down in total darkness to catch the night views should try to go on this trail first during daytime, or go with someone who has gone up before.

- Starting from Wong Tai Sin, close to the entrance of the Lion Rock trail preferred by the locals, hikers face a nearly 400-m elevation gain (from 100m to 495m) consisting mostly of stairs and rocks to the top. On a hot and humid summer day, bring as much water as possible.

Wildlife

There are monkeys that may attempt to take away food from hikers as they recognize that plastic bags may contain food.[31][32] The monkeys are called Longtailed Macaques and are descendants of pets released into the wild in the 1920s.[33] The government introduced these macaques to protect the trees that surround reservoirs near Lion Rock from a vine called Mikania micrantha, as the macaques loved to feed on this vine.[34]

Venomous snakes are active in the evening, especially in the late summer or early autumn just before hibernation. The venomous but rarely-lethal Bamboo Pit Viper, among other venomous snakes, is seen in the area mostly at night, so try to avoid stepping into bushes or thick grass where they might be lurking.[35] The Bamboo Pit Viper accounts for over 90% of all snake bites in Hong Kong.[36]

Gallery

General view of Kowloon circa 1868, with Lion Rock in the background overlooking the Qing-era Kowloon Walled City.

Kwun Tong Road and Lion Rock in 1945 (upper right corner)

Banner hung up on the Lion Rock in support of the 2014 Hong Kong protests.

See also

References

- "District Council Constituency Boundaries - Sha Tin District"(PDF) . Electoral Affairs Commission. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- "Lion Rock". www.afcd.gov.hk. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Kowloon Granite - Klk". www.cedd.gov.hk. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Wong, Maggie Hiufu (10 October 2018). "Lion Rock: Hong Kong's most beautiful climbing destination". CNN Travel. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Lion Rock spirit still casting its spell on Hong Kong". South China Morning Post. 22 April 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- none. "Hong Kong unmasked: how the protests hit home in one neighborhood". Reuters. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- Visual Identity, Brand Hong Kong

- Tatlow, Didi Kirsten (23 October 2014). "A Banner on a Hong Kong Landmark Speaks of Democracy and Identity". Sinosphere Blog. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Giant pro-democracy banner removed from Hong Kong's famous Lion Rock". South China Morning Post. 24 October 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "Chris Bonington talks life and loss on a Hong Kong hike". South China Morning Post. 11 July 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- Liu, Shuyong (1997). An Outline History of Hong Kong. Foreign Languages Press. p. 18. ISBN9787119019468 .

- Faure, David; Hayes, James; Birch, Alan. From Village to City: Studies In the Traditional Roots of Hong Kong Society. Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong. p. 5. ASINB0000EE67M . OCLC13122940 .

- "Hong Kong Landscape and Human Impacts". HK Government CEDD Department.

- "LCQ11: Safety of hikers". www.info.gov.hk. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- Standard, The. "Death lurks in 16 scenic spots". The Standard. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- "Why so many people get into trouble when hiking in Hong Kong". South China Morning Post. 9 December 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- "Campaigner urges public to 'selfie responsibly' following Lion Rock accident". Hong Kong Free Press HKFP. 18 March 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- "Hong Kong hiker falls to his death from cliff on Lion Rock after 'trying to take photo'". South China Morning Post. 13 March 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- "行獅子山 抄捷徑 女子墮崖死". Apple Daily 蘋果日報. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- "獅子山有男子墮崖送院不治". news.now.com (in Chinese). Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- "女子疑行山失足跌死 伏屍獅子山斜坡". hk.news.yahoo.com (in Chinese). Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- HK, Alien Hiker (1 April 2007). "獅子山墮崖". Hiker's Corner (in Chinese). Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Coverpage - MMIS". mmis.hkpl.gov.hk. p. 7. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- "行獅子山 抄捷徑 女子墮崖死". Apple Daily 蘋果日報 (in Chinese). Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- "獨攀獅子山 青年墮崖亡 - 香港文匯報". paper.wenweipo.com. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- 林振華, 蔡正邦, 賴雯心, 陳浩然 (30 May 2019). "【魂斷獅子山】73歲翁疑墮崖 GFS直升機搜索五小時尋回屍體". 香港01 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- "為影獅頭粉身碎骨 男子墮400米崖底亡". 太陽報. 13 March 2016. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- "獅子山驚現屍體 藍衫女子伏屍山坡". Apple Daily 蘋果日報. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "獅子山山頭有男子疑墮崖死亡 直升機吊起遺體 - 香港經濟日報 - TOPick - 新聞 - 社會". topick.hket.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- 蘋果日報. "女子獅子山墮崖不治". Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- "Wild Monkeys of Hong Kong". www.afcd.gov.hk. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- "Hong Kong's monkey population increasingly harassing hikers and residents for food". South China Morning Post. 3 August 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Lion Rock". www.afcd.gov.hk. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Then & now: what the macaque?". South China Morning Post. 16 September 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- "Venomous Land Snakes in Hong Kong". www.afcd.gov.hk. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- HK, Southside (17 May 2017). "Be prepared: The most common snakes in Hong Kong". Southside Magazine. Retrieved 5 October 2019.