Herzegovina

Herzegovina (/ˌhɛərtsɪˈɡoʊvɪnə/ or /ˌhɜːrtsəɡoʊˈviːnə/; Serbo-Croatian: Hercegovina / Херцеговина, [xɛ̌rtsɛɡov̞ina]) is the southern and smaller of two main geographical regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the other being Bosnia. It has never had strictly defined geographical or cultural-historical borders, nor has it ever been defined as an administrative whole in the geopolitical and economic subdivision of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Bosnia, the larger of the two regions, lies to the west and north of Herzegovina, while the Croatian region of Dalmatia lies to the south-southwest, and Montenegro lies to the east-southeast. The land area of Herzegovina is around 11,500–12,300 km2 (4,400–4,700 sq mi), or around 23–24% of the country. The largest city is Mostar, in the center of the region. Other large settlements include Trebinje, Široki Brijeg, Ljubuški, Čapljina, Konjic and Posušje.

Contents

Etymology

The name Hercegovina (Herzegovina in English) stems from the archaic Serbo-Croatian term, Herceg, borrowed from GermanHerzog (the German term for a duke; Serbo-Croatian: vojvoda), and means a land ruled and/or owned by a herceg, thus literally means duke's land (hercegovina). The first among the Kosača dukes to use the title herceg instead of duke was Stjepan Vukčić Kosača, who became Herzog of Hum in 1449/50. In December 1481, the lands of Stjepan Vukčić's successors were finally occupied by Ottoman forces. The Ottomans were the first to officially use the name Herzegovina (Hersek) for the region in their administrative affairs in 1454, and established a sanjak bearing that name in 1470, the Sanjak of Herzegovina, with its first seat at Foča.[2][3][4]

The name Herzegovina is the most important and indelible Herceg Stjepan's legacy, unique within the entire Serbo-Croatian speaking world of the Balkans, of one medieval person giving his name, or more precisely his noble title, which in the last few years of his life became literally inseparable from his name, to an entire region previously called Humska zemlja, or Hum for short,[5] which still exists today with the name Bosnia and Herzegovina.[6][7]

Although this is just a superficial understanding, because the appearance of the name Herzegovina, recorded as early as 1 February 1454, in a letter written by the Ottoman commander Esebeg from Skopje,[6] can not be attributed to Herceg Stjepan alone, as his title was not of decisive importance after all.[7] Far more crucial was a well-known Ottoman custom to call newly acquired lands by the names of its earlier lords. It was enough for the Ottomans to conquer Stjepan's land as a whole, to start calling it Herzegovina. Also, Herceg-Stjepan did not establish this province as a feudal and political unit of the Bosnian state, that honor befell Grand Duke of Bosnia, Vlatko Vuković, who received it from King Tvrtko I, while Sandalj Hranić expanded it and reaffirmed the Kosača family supremacy.[7]

History

Medieval period

Slavs settled in the Balkans in the 7th century. What later became known as Herzegovina was divided between Croatia, Zachlumia and Travunija in the Early Middle Ages. Parts of the region were later ruled by various medieval rulers, with the eastern part mostly within Medieval Serbia, and the western part in the Kingdom of Croatia. During the 13th and 14th centuries the Bosnian bansStjepan I Kotromanić and Stjepan II Kotromanić joined these regions to the Bosnian state, with the King Tvrtko I Kotromanić extending territories even further, beyond what is modern-day Herzegovina proper.[1] During these times, parts of Herzegovina, or Hum, as it was called at the time, were ruled by powerful Bosnian magnates of Kosača family and its branch clans, namely Vuković, headed by Vlatko Vuković, who received it from the King Tvrtko I as an award for his service as a supreme commander of the Bosnian army, and Hranić, headed by Grand Duke of Bosnia, Sandalj Hranić. Another powerful Bosnian noble family, Pavlović, whose seat was near Rogatica in Drina county, including holdings in Drina and parts of Vrhbosna, also sheared a some of the territories in Hum centered around Trebinje.[8][9]Stjepan Vukčić , Sandalj's nephew, inherited lordship over the Hum, and was the last Bosnian nobleman who had effective control over the province (zemlja) before Ottoman conquest. He titled himself Duke of Hum and Primorje, Bosnian Grand Duke, Knyaz of Drina, and later Herzog of Saint Sava, Lord of Hum and Bosnian Grand Duke, Knyaz of Drina and the rest. Following the Ottomans conquest and fall of Bosnian Kingdom, Hum or Humska zemlja became known as Hercegovina (transl. Herzegovina), which literally means Herzog's land.[6]

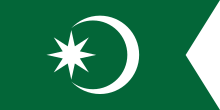

Ottoman period

In 1482, the lands of Stefan Vukčić's successors were occupied by Ottoman forces. The Ottomans were the first to begin officially using the name Herzegovina (Hersek) for the region.

The Bosnian beylerbey Isa-beg Ishaković mentioned the name in a letter from 1454. In the Ottoman Empire, Herzegovina was organized as a sanjak, the Sanjak of Herzegovina, within the Bosnia Eyalet. According to the Turkish census of Herzegovina from 1477, some villages were mentioned as being "in the possession of Vlachs," while others, were listed as "Serb settlements" and mostly deserted.[10] According to Ottoman defters, at the end of 15th century in Herzegovina were at least 35,000 of Vlachs.[11]

During the Long War (1591–1606), Serbs rose up in Herzegovina (1596–97), but they were quickly suppressed after their defeat at the field of Gacko.

The Candian War of 1645 to 1669 caused great damage to the region as the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire fought for control over Dalmatia and coastal Herzegovina.

As a result of the Treaty of Karlowitz of 1699, the Ottomans gained access to the Adriatic Sea through the Neum-Klek coastal area. The Republic of Dubrovnik ceded this to distance themselves from the Venetian Republic's influence. The Ottomans benefitted from this in gaining the region's salt.

As a result of the Bosnian Uprising (1831–32), the Vilayet was split to form the separate Herzegovina Eyalet, ruled by semi-independent vizierAli-paša Rizvanbegović . After his death, the eyalets of Bosnia and Herzegovina were merged.

The new joint entity was after 1853 commonly referred to as Bosnia and Herzegovina. Serbs in the region revolted against the Ottomans (1852–62) and were aided by the Montenegrins, who sought the liberation of the Serb people from Ottoman rule.

The Herzegovinian Serbs frequently rose up against the Ottoman rule; culminating in the Herzegovina Uprising (1875-78), which was supported by the Principality of Serbia and Montenegro.

Montenegro did succeed in liberating and annexing large parts of Herzegovina before the Berlin Congress of 1878, including the Nikšić area; the historical Herzegovina region annexed to Montenegro is known as East or Old Herzegovina.

Modern history

As a result of the Treaty of Berlin (1878), Herzegovina, along with Bosnia, were occupied by Austria-Hungary, only nominally remaining under Ottoman rule.

The historical Herzegovina region in the Principality of Montenegro was known as East or Old Herzegovina. The Serb population of Herzegovina and Bosnia hoped for annexation to Serbia and Montenegro. The Franciscan order opened the first university in Herzegovina in 1895 in Mostar.

In 1908, Austria-Hungary annexed the province, leading to the Bosnian Crisis, an international dispute which barely failed to precipitate a world war immediately, and was an important step in the buildup of international tensions during the years leading up to the First World War. The assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand came as a direct result of the resentment of the Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina against Austro-Hungarian rule.

During World War I, Herzegovina was a scene of inter-ethnic conflict. During the war, the Austro-Hungarian government formed Šuckori, Muslim para-militia units. Šuckori units were especially active in Herzegovina. Persecution of Serbs conducted by the Austro-Hungarian authorities was the "first incidence of active 'ethnic cleansing' in Bosnia and Herzegovina".[12]

In 1918, Herzegovina became a part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later renamed Kingdom of Yugoslavia). In 1941 Herzegovina fell once again under the rule of the fascistIndependent State of Croatia . During World War II, Herzegovina was a battleground between fascist Croat Ustaše, royalist Serb Četniks, and the communist Yugoslav Partisans; Herzegovina was a part of the Independent State of Croatia, administratively divided into the counties of Hum and Dubrava, then in 1945, Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina became one of the republics of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. It remained so until the breakup of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. During the Bosnian War, large parts of western and central Herzegovina came under control of the Croat republic of Herzeg-Bosnia (which later joined the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina) while eastern Herzegovina became a part of Republika Srpska.

Geography

Herzegovina is a southernregion of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Its borders and territory have never been geographically or culturally-historically strictly defined, nor has ever been defined as an administrative whole in the geopolitical and economic subdivision of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which is also true considering regionalisation in the modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The larger of two Bosnia and Herzegovina regions, Bosnia, is to the west and north of Herzegovina, and the border between two regions, Herzegovina and Bosnia, is unclear as it has never been strictly defined. To the south-southwest of region lies Croatian region of Dalmatia, and to the east-southeast is Montenegro.

The land area is c. 11,500 km2 (4,400 sq mi),[13] or around 23% of the total area of the present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, to c. 12,300 km2 (4,700 sq mi), or around 24% of the country.[1]

The terrain of Herzegovina is mostly hilly karst with high mountains in the north such as Čvrsnica and Prenj, except for the central valley of the river Neretva. The upper reaches of the River Neretva lie in northern Herzegovina, a heavily forested area with fast-flowing rivers and high mountains. Konjic and Jablanica lie in this area.

The Neretva rises on Lebršnik Mountain, close to the Montenegro border, and as the river flows west, it enters Herzegovina. The entire upper catchment of the Neretva constitutes a precious ecoregion with many endemic and endangered species. The river carves through the precipitous karst terrain, providing excellent opportunities for rafting and kayaking, while the spectacular scenery of the surrounding mountains and forests is a challenging hiking terrain. The Neretva's tributaries in the upper reaches are mostly short, due to the mountainous terrain: the River Rakitnica has cut a deep canyon, its waters being one of the least explored areas in this part of Europe. The Rakitnica flows into Neretva upstream from Konjic. The Neretva then flows northwest, through Konjic. It enters the Jablanica Reservoir (Jablaničko jezero), one of the largest in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The lake ends near the town of Jablanica. From here on, the Neretva turns southward, continuing toward the Adriatic Sea. With the mountains lining its shores gradually receding, the Neretva enters a valley where the city of Mostar lies. It flows under the old bridge (Stari most) and continues, now wider, toward the town of Čapljina and the Neretva Delta in Croatia before emptying into the Adriatic Sea.

Cities and towns

The largest city is Mostar, in the center of the region. Other larger towns include Trebinje, Stolac, Široki Brijeg, Posušje, Ljubuški, Grude, Konjic, and Čapljina.[1]

Mostar is the best-known urban area and the official capital. It is the only city with over 100,000 citizens. There are no other large cities in Herzegovina, though some have illustrious histories.[1]

Stolac, for example, is perhaps Herzegovina's oldest city. Settlements date from the Paleolithic period (Badanj Cave). An Illyrian tribe lived in the city of Daorson. There were several Roman settlements alongside the Bregava River and medieval inhabitants left large stone grave monuments called stećak in Radimlja. Trebinje, on the Trebišnjica River, is the southernmost city in Bosnia and Herzegovina, near the Montenegro border.[1]

Čapljina and Ljubuški are known for their history and their rivers; the village of Međugorje has religious importance for many Roman Catholics.

Administration

In the modern state of Bosnia and Herzegovina, area of Herzegovina is divided between two entities, Republika Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Republika Srpska's part of Herzegovina, commonly referred to as East Herzegovina or, as of late, "Trebinje Region", is administratively divided into municipalities of Berkovići, Bileća, Gacko, Istočni Mostar, Ljubinje, Nevesinje, and Trebinje.[1]

Within the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Herzegovina is administratively divided between the cantons of Herzegovina-Neretva and West Herzegovina.[1]

East Herzegovina or "Trebinje Region" in Republika Srpska

Population

The locals of Herzegovina are known by the demonymHerzegovinians (Serbo-Croatian: Hercegovci / Херцеговци; singular masculine:Hercegovac / Херцеговац, feminine:Hercegovka / Херцеговка), which they prefer to be referred to as rather than Bosnians[citation needed]. While the population of Herzegovina throughout history has been ethnically mixed, the Bosnian War in the 1990s resulted in mass ethnic cleansing and large-scale displacement of people. The last pre-war census in 1991 recorded a population of 437,095 inhabitants.

- Croats generally populate the areas closest to the Croatian border focused on Mostar, Ljubuški, Široki Brijeg, Čitluk, Grude, Posušje, Čapljina, Neum, Stolac, Ravno, Livno, Tomislavgrad, Kupres and Prozor-Rama.

- Bosniaks mainly live in the areas along the Neretva, such as Mostar, Konjic and Jablanica, to a significant extent in Stolac, Čapljina, and to a lesser extent in Nevesinje, Gacko, Trebinje.

- Serbs are the majority in East Herzegovina, including the municipalities of Berkovići, Bileća, Gacko, Istočni Mostar, Ljubinje, Nevesinje, and Trebinje.

Culture

Monuments

The region has rich history and diverse culture, with variety of important monuments of cultural-historical heritage, such as the following cultural monuments; Mogorjelo, Stari most, Stećci and Tekija.[1]

Religion

The Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina guarantees freedom of religion,[15]

- Eparchy of Zahumlje and Herzegovina of the Serbian Orthodox Church

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Mostar-Duvno and Roman Catholic Diocese of Trebinje-Mrkan

- Islam (See: Islamic Community of Bosnia and Herzegovina)

Music

Bosnia and Herzegovina folk costumes from Tomislavgrad

Tourism

Herzegovina's natural landmarks include many features.[1]

- The falls of Kravica, on the Trebižat river, consist of several waterfalls near the city of Ljubuški and a popular spot for the local people, to take a bath in the hot Herzegovinian weather, or just to enjoy the view.

- The Hutovo Blato is a bird reserve, one of the most important in Europe and a gathering place for many international ornithologists.

- Vjetrenica is a cave system and a unique ecosystem. It is located near the border with Croatia, in Popovo Polje in the Ravno municipality. The cave has not been explored totally yet, but it is open to visitors. A large number of endemic cave-dwelling species have been discovered there, and new ones can be expected to be discovered still.

- Blagaj is also known as the origin of the Buna River, inside a cave system.

- Neum at the Adriatic Sea, Bosnia and Herzegovina's only coastal town, is also a tourist attraction.

- Međugorje has one of the most visited sites in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Image gallery

References

- "3. Hercegovačka regija". Regionalna strategija ekonomskog razvoja Hercegovine(pdf / html) . Regionalna razvojna agencija za Hercegovinu (REDAH.ba) – in conjunction with the EU RED Project (in Serbo-Croatian). Bosna i Hercegovina. November 2004. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- Ćirković, Sima M. (1964). "Chepter 7: Slom Bosanske države; Part 3: Pad Bosne". Istorija srednjovekovne bosanske države (in Serbian). Srpska književna zadruga. pp. starting with 336. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- John V.A. Fine, "The Medieval and Ottoman Roots of Modern Bosnian Society", in Mark Pinson, ed., The Muslims of Bosnia-Herzegovina: Their Historic Development from the Middle Ages to the Dissolution of Yugoslavia, Harvard Middle East Monographys 28, Harvard University Center for Middle Eastern Studies, 2nd ed, 1996 ISBN0932885128 , p. 11

- B. Djurdjev, "Bosna" in Encyclopaedia of Islam 2nd ed. P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W. P. Heinrichs, eds. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0126, 2012.

- Vego 1982, p. 48: "Tako se pojam Humska zemlja postepeno gubi da ustupi mjesto novom imenu zemlje hercega Stjepana — Hercegovini."

- Vego 1982, p. 48.

- Ćirković 1964a, p. 272.

- "Borak (Han-stjenički plateau) necropolis with stećak tombstones in the village of Burati, the historic site". Commission to preserve national monuments (in Bosnian). Commission to preserve national monuments. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Maslo, Amer. "M.A. Thesis: "Slavni i velmožni gospodin knez Pavle Radinović" (available for download at faculty website)"(PDF) . www.ff.unsa.ba (in Bosnian). Faculty of Philosophy of University of Sarajevo – History Department. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Sima Ćirković; (2004) The Serbs p. 130; Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN0631204717

- Noel Malcolm; (1995), Povijest Bosne – kratki pregled p. 105; Erasmus Gilda, Novi Liber, Zagreb, Dani-Sarajevo, ISBN953-6045-03-6

- Lampe 2000, p. 109

- "Administrativno uređenje Hercegovine od 1945. do 1952. godine"Archived 2017-07-29 at the Wayback Machine by Adnan Velagić, Most – časopis za obrazovanje, nauku i kulturu, No. 191 (October 2005), pp. 82–84. ISSN0350-6517 .

- Ethnic composition of Bosnia-Herzegovina population, by municipalities and settlements, 1991. Bilten no.234. Sarajevo: Zavod za statistiku Bosne i Hercegovine. 1991.

- "Freedom of religion Law..., Official Gazette of B&H 5/04". Mpr.gov.ba. Archived from the original(PDF) on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

Bibliography

- Bataković, Dušan T. (1996). The Serbs of Bosnia & Herzegovina: History and Politics. Paris: Dialogue. ISBN9782911527104 .

- Ćirković, Sima (1964a). Herceg Stefan Vukčić-Kosača i njegovo doba (in Serbian). Naučno delo SANU.

- Ćirković, Sima (1964). Историја средњовековне босанске државе (in Serbian). Srpska književna zadruga.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN9781405142915 .

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN0472081497 .

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN0472082604 .

- Klaić, Nada (1989). Srednjovjekovna Bosna: Politički položaj bosanskih vladara do Tvrtkove krunidbe (1377. g.). Zagreb: Grafički zavod Hrvatske. ISBN9788639901042 .

- Lampe, John R. (2000). Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-77401-7 .

- Vego, Marko (1982). Postanak srednjovjekovne bosanske države (in Serbo-Croatian). Svjetlost.