Cliff

In geography and geology, a cliff is an area of rock which has a general angle defined by the vertical, or nearly vertical. Cliffs are formed by the processes of weathering and erosion, with the effect of gravity. Cliffs are common on coasts, in mountainous areas, escarpments and along rivers. Cliffs are usually composed of rock that is resistant to weathering and erosion. The sedimentary rocks that are most likely to form cliffs include sandstone, limestone, chalk, and dolomite. Igneous rocks such as granite and basalt also often form cliffs.

An escarpment (or scarp) is a type of cliff formed by the movement of a geologic fault, a landslide, or sometimes by rock slides or falling rocks which change the differential erosion of the rock layers.

Most cliffs have some form of scree slope at their base. In arid areas or under high cliffs, they are generally exposed jumbles of fallen rock. In areas of higher moisture, a soil slope may obscure the talus. Many cliffs also feature tributary waterfalls or rock shelters. Sometimes a cliff peters out at the end of a ridge, with mushroom rocks or other types of rock columns remaining. Coastal erosion may lead to the formation of sea cliffs along a receding coastline.

The Ordnance Survey distinguishes between around most cliffs (continuous line along the topper edge with projections down the face) and outcrops (continuous lines along lower edge).

Etymology

Cliff comes from the Old English word clif of essentially the same meaning, cognate with Dutch, Low German, and Old Norse klif 'cliff'.[1] These may in turn all be from a Romance loanword into Primitive Germanic that has its origins in the Latin forms clivus / clevus ("slope" or "hillside").[2][3]

Large and famous cliffs

Given that a cliff does not need to be exactly vertical, there can be ambiguity about whether a given slope is a cliff or not and also about how much of a certain slope to count as a cliff. For example, given a truly vertical rock wall above a very steep slope, one could count just the rock wall or the combination. Listings of cliffs are thus inherently uncertain.

Some of the largest cliffs on Earth are found underwater. For example, an 8,000 m drop over a 4,250 m span can be found at a ridge sitting inside the Kermadec Trench.

The highest very steep non-vertical cliffs in the world are Nanga Parbat's Rupal Face and Gyala Peri's southeast face, which both rise approximately 4,600 m, or 15,000 ft, above their base. According to other sources, the highest cliff in the world, about 1,340 m high, is the east face of Great Trango in the Karakoram mountains of northern Pakistan. This uses a fairly stringent notion of cliff, as the 1,340 m figure refers to a nearly vertical headwall of two stacked pillars; adding in a very steep approach brings the total drop from the East Face precipice to the nearby Dunge Glacier to nearly 2,000 m.

The location of the world's highest sea cliffs depends also on the definition of 'cliff' that is used. Guinness World Records states it is Kalaupapa, Hawaii,[5] at 1,010 m high. Another contender is the north face of Mitre Peak, which drops 1,683 m to Milford Sound, New Zealand.[6] These are subject to a less stringent definition, as the average slope of these cliffs at Kaulapapa is about 1.7, corresponding to an angle of 60 degrees, and Mitre Peak is similar. A more vertical drop into the sea can be found at Maujit Qaqarssuasia (also known as the 'Thumbnail') which is situated in the Torssukátak fjord area at the very tip of South Greenland and drops 1,560 m near-vertically.[7]

Considering a truly vertical drop, Mount Thor on Baffin Island in Arctic Canada is often considered the highest at 1370 m (4500 ft) high in total (the top 480 m (1600 ft) is overhanging), and is said to give it the longest vertical drop on Earth at 1,250 m (4,100 ft). However, other cliffs on Baffin Island, such as Polar Sun Spire in the Sam Ford Fjord, or others in remote areas of Greenland may be higher.

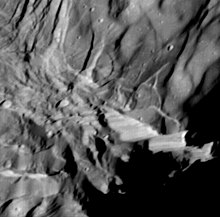

The highest cliff in the solar system may be Verona Rupes, an approximately 20 km (12 mi) high fault scarp on Miranda, a moon of Uranus.

List

The following is an incomplete list of cliffs of the world.

Africa

Above Sea

- Anaga's Cliffs, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain, 592 m (1,942 ft) above Atlantic Ocean

- Cape Hangklip, Western Cape, South Africa, 453.1 m (1,487 ft) above False Bay, Atlantic Ocean

- Cape Point, Western Cape, South Africa, 249 m (817 ft) above Atlantic Ocean

- Chapman's Peak, Western Cape, South Africa, 596 m (1,955 ft) above Atlantic Ocean

- Karbonkelberg, Cape Town, Western Cape, South Africa, 653 m (2,142 ft) above Hout Bay, Atlantic Ocean

- Kogelberg, Western Cape, South Africa, 1,289 m (4,229 ft) above False Bay, Atlantic Ocean

- Los Gigantes, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain, 637 m (2,090 ft) above Atlantic Ocean

- Table Mountain, Cape Town, Western Cape, South Africa, 1,086 m (3,563 ft) above Atlantic Ocean

Above Land

- Innumerable peaks in the Drakensberg mountains of South Africa are considered cliff formations. The Drakensberg Range is regarded, together with Ethiopia's Simien Mountains, as one of the two finest erosional mountain ranges on Earth. Because of their near-unique geological formation, the range has an extraordinarily high percentage of cliff faces making up its length, particularly along the highest portion of the range.[citation needed] This portion of the range is virtually uninterrupted cliff faces, ranging from 600 m (2,000 ft) to 1,200 m (3,900 ft) in height for almost 250 km (160 mi). Of all, the "Drakensberg Amphitheatre" (mentioned above) is most well known.[citation needed] Other notable cliffs include the Trojan Wall, Cleft Peak, Injisuthi Triplets, Cathedral Peak, Monk's Cowl, Mnweni Buttress, etc. The cliff faces of the Blyde River Canyon, technically still part of the Drakensberg, may be over 800 m (2,600 ft), with the main face of the Swadini Buttress approximately 1,000 m (3,300 ft) tall.

- Drakensberg Amphitheatre, South Africa 1,200 m (3,900 ft) above base, 5 km (3.1 mi) long. The Tugela Falls, the world's second tallest waterfall, falls 948 m (3,110 ft) over the edge of the cliff face.

- Karambony, Madagascar, 380 m (1,250 ft) above base.

- Mount Meru, Tanzania Caldera Cliffs, 1,500 m (4,900 ft)

- Tsaranoro, Madagascar, 700 m (2,300 ft) above base

America

Several big granite faces in the Arctic region vie for the title of 'highest vertical drop on Earth', but reliable measurements are not always available. The possible contenders include (measurements are approximate):

Mount Thor, Baffin Island, Canada; 1,370 m (4,500 ft) total; top 480 m (1600 ft) is overhanging. This is commonly regarded as being the largest vertical drop on Earth [2][2][citation needed]ot:leapyear at 1,250 m (4,100 ft).

of Baffin Island, rises 4,300 ft above the flat frozen fjord, although the lower portion of the face breaks from the vertical wall with a series of ledges and buttresses.[8]

Other notable cliffs include:

- Ättestupan Cliff, northern side of Kaiser Franz Joseph Fjord, Greenland 1,300 m (4,300 ft)[13]

- Big Sandy Mountain, east face buttress, Wind River Range, Wyoming, 550 m

- Calvert Cliffs along the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland, U.S. 25 m

- Cap Éternité of Saguenay River, Quebec, Canada, 347 m

- All faces of Devils Tower, Wyoming, United States, 195 m

- Doublet Peak, southwest face, Wind River Range, Wyoming, United States, 370 m

- El Capitan, Yosemite Valley, California, United States; 900 m (3,000 ft)

- Grand Teton, north face Teton Range, Wyoming 760 m (2,490 ft)

- Northwest Face of Half Dome, near El Capitan, California, United States; 1,444 m (4,737 ft) total, vertical portion about 610 m (2,000 ft)

- Longs Peak Diamond, Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado, United States, 400 m

- Mount Asgard, Baffin Island, Canada; vertical drop of about 1,200 m (4,000 ft).

- Mount Siyeh, Glacier National Park (U.S.) north face, 1,270 m (4,170 ft)

- The North Face of North Twin Peak, Rocky Mountains, Alberta, Canada, 1,200 m

- The west face of Notch Peak in the House Range of southwestern Utah, U.S.; a carbonate rock pure vertical drop of about 670 m (2,200 ft), with 4,450 feet (1,356 m) from the top of the cliff to valley floor (bottom of the canyon below the notch)

- Painted Wall in Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, Colorado, United States; 685 m (2,250 ft)

- Raftsmen's Acropolis, a rock face of the Montagne des Érables, Quebec, Canada, 800 m

- Rockwall, Kootenay National Park, British Columbia, Canada, 30 km of mostly unbroken cliffs up to 900 m [14]

- Royal Gorge cliffs, Colorado, United States, 350 m

- Faces of Shiprock, New Mexico, United States, 400 m

- All walls of the Stawamus Chief, Squamish, British Columbia, Canada, up to 500 m

- Temple Peak, east face, Wind River Range, Wyoming, 400 m

- Temple Peak East, north face, Wind River Range, Wyoming, 450 m

- Toroweap (a.k.a. Tuweep), Grand Canyon, Arizona, United States; 900 m (3,000 ft)

- Uncompahgre Peak, northeast face, San Juan Range, Colorado, 275 m (550 m rise above surrounding plateau)

- East face of the West Temple in Zion National Park, Utah, United States believed to be the tallest sandstone cliff in the world,[15] 670 m

- All faces of Auyan Tepui, along with all other Tepuis, Venezuela, Brazil, and Guyana, Auyan Tepui is about 1,000 m (location of Angel Falls) (the falls are 979 m, the highest in the world)

- All faces of Cerro Chalten (Fitz Roy), Patagonia, Argentina-Chile, 1200 m

- All faces of Cerro Torre, Patagonia, Chile-Argentina

- Pão de Açúcar/Sugar Loaf, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 395 m

- Pared de Gocta, Peru, 771 m

- Pared Sur Cerro Aconcagua. Las Heras, Mendoza, Argentina, 2,700 m

- Pedra Azul, Pedra Azul State Park, Espirito Santo, Brazil, 540 m

- Scratched Stone (Pedra Riscada), São José do Divino/MG, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 1,480 m

- Faces of the Torres del Paine group, Patagonia, Chile, up to 900 m

Asia

Above Sea

- Qingshui Cliff, Xiulin Township, Hualien County, Taiwan averaging 800 m above Pacific Ocean. The tallest peak, Qingshui Mountain, rises 2408 m directly from the Pacific Ocean.

- Ra's Sajir, Oman, 900 m (3,000 ft) above the Arabian Sea

- Theoprosopon, between Chekka and Selaata in north Lebanon jutting into the Mediterranean.

- Tōjinbō, Sakai, Fukui prefecture, Japan 25 m above Sea of Japan

Above Land

- Various cliffs in the Ak-Su Valley of Kyrgyzstan are high and steep.

- Baintha Brakk (The Ogre), Panmah Muztagh, Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan, 2,000 m

- Gyala Peri, southeast face, Mêdog County, Tibet, China, 4,600 m

- Hunza Peak south face, Karakoram, Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan, 1,700 m

- K2 west face, Karakoram, Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan, 2900m

- The Latok Group, Panmah Muztagh, Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan, 1,800 m

- Lhotse northeast face, Mahalangur Himal, Nepal, 2900m

- Lhotse south face, Mahalangur Himal, Nepal, 3200 m

- Meru Peak, Uttarakhand, India, 1200 m

- Nanga Parbat, Rupal Face, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan, 4,600 m

- Qingshui Cliff, Xiulin Township, Hualien County, Taiwan averaging 800 m above Pacific Ocean. The tallest peak, Qingshui Mountain, rises 2408 meters directly from the Pacific Ocean.

- Ramon Crater, Israel, 400 m

- Shispare Sar southwest face, Karakoram, Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan, 3,200 m

- Spantik northwest face, Karakoram, Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan, 2,000 m

- Trango Towers: East Face Great Trango Tower, Baltoro Muztagh, Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan, 1,340 m (near vertical headwall), 2,100 m (very steep overall drop from East Summit to Dunge Glacier). Northwest Face drops approximately 2,200 m to the Trango Glacier below, but with a taller slab topped out with a shorter overhanging headwall of approximately 1,000 m. The Southwest "Azeem" Ridge forms the group's tallest steep rise of roughly 2,286 m (7,500 ft) from the Trango Glacier to the Southwest summit.

- Uli Biaho Towers, Baltoro Glacier, Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan

- Ultar Sar southwest face, Karakoram, Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan, 3,000 m

- World's End, Horton Plains, Nuwara Eliya, Sri Lanka. It has a sheer drop of about 4000 ft (1200 m)

- Various cliffs in Zhangjiajie National Forest Park, Hunan Province, China. The cliffs can get to around 1,000 ft (300 m).

Europe

Above Sea

- Beachy Head, England, 162 m above the English Channel

- Beinisvørð, Faroe Islands, 470 m above North Atlantic

- Belogradchik Rocks, Bulgaria - up to 200 m high sandstone towers

- Benwee Head Cliffs, Erris, Co. Mayo, Ireland, 304 m above Atlantic Ocean

- Cabo Girão, Madeira, Portugal, 589 m above Atlantic Ocean

- Cap Canaille, France, 394 m above Mediterranean sea is the highest sea cliff in France

- Cape Enniberg, Faroe Islands, 750 m above North Atlantic

- Conachair, St Kilda, Scotland 427 m above Atlantic Ocean, highest sea cliff in the UK

- Croaghaun, Achill Island, Ireland, 688 m above Atlantic Ocean

- Dingli Cliffs, Malta, 250 m above Mediterranean sea

- Dvuglav, Rila Mountain, Bulgaria 460 m (south face)

- Étretat, France, 84 m above the English Channel

- Faneque, Gran Canaria, Spain, 1027 m above Atlantic Ocean

- Hangman cliffs, Devon 318 m above Bristol Channel is the highest sea cliff in England

- High Cliff, between Boscastle and St Gennys, 223 m above Celtic Sea[16]

- Hornelen, Norway, 860 m above Skatestraumen

- Hvanndalabjarg, Ólafsfjörður, Iceland, 630 m above Atlantic Ocean

- Jaizkibel, Spain, 547 m above the Bay of Biscay

- Kaliakra cliffs, Bulgaria, more than 70 m above the Black Sea

- The Kame, Foula, Shetland, 376 m above the North Atlantic, second highest sea cliff in the UK

- Le Tréport, France, 110 m above the English Channel

- Cliffs of Moher, Ireland, 217 m above Atlantic Ocean

- Møns Klint, Denmark, 143 m above Baltic Sea

- Monte Solaro, Capri, Italy, 589 m above the Mediterranean Sea

- Ontika Limestone cliff, Estonia, 55 m above Baltic Sea.

- Preikestolen, Norway, 604 m above Lysefjorden

- Slieve League, Ireland, 601 m above Atlantic Ocean

- Snake Island, Ukraine, 41 m above the Black Sea

- Vixía Herbeira, Northern Galicia, Spain, 621 m above Atlantic Ocean

- White cliffs of Dover, England, 100 m above the Strait of Dover

Above Land

- The six great north faces of the Alps (Eiger 1,500 m, Matterhorn 1,350 m, Grandes Jorasses 1,100 m, Petit Dru 1,000 m, and Piz Badile 850 m, Cima Grande di Lavaredo 450 m)

- Giewont (north face), Tatra Mountains, Poland, 852 m above Polana Strążyskaglade

- Kjerag, Norway 984 m.

- Mięguszowiecki Szczyt north face rises to 1,043 m above Morskie Oko lake level, High Tatras, Poland

- Troll Wall, Norway 1,100 m above base

- Vihren peak north face, Pirin Mountain, Bulgaria 460 m to the (Golemiya Kazan)

- Vratsata, Vrachanski Balkan Nature Park, Bulgaria 400 m [17]

Submarine

- Bouldnor Cliff - the waters of the coast of the Isle of Wight[18]

Oceania

Above Sea

- Ball's Pyramid, a sea stack 562m high and only 200m across at its base

- The Elephant, New Zealand, has cliffs falling approx 1180m into Milford Sound, and a 900m drop in less than 300m horizontally

- Great Australian Bight

- Kalaupapa, Hawaii, 1,010 m above Pacific Ocean

- The Lion, New Zealand, 1,302 m above Milford Sound (drops from approx 1280m to sea level in a very short distance)

- Lovers Leap, Highcliff, and The Chasm, on Otago Peninsula, New Zealand, all 200 to 300 m above the Pacific Ocean

- Mitre Peak, New Zealand, 1,683 m above Milford Sound

- Tasman National Park, Tasmania, has 300m dolerite sea cliffs dropping directly to the ocean in columnar form

- The Twelve Apostles (Victoria). A series of sea stacks in Australia, ranging from approximately 50 to 70 m above the Bass Strait

- Zuytdorp Cliffs in Western Australia

Above Land

- Mount Banks in the Blue Mountains National Park, New South Wales, Australia: west of its saddle there is a 490 m fall within 100 M horizontally.[19]

As habitat

Cliff landforms provide unique habitat niches to a variety of plants and animals, whose preferences and needs are suited by the vertical geometry of this landform type. For example, a number of birds have decided affinities for choosing cliff locations for nesting,[20] often driven by the defensibility of these locations as well as absence of certain predators.

Flora

The population of the rareBorderea chouardii, during 2012, existed only on two cliff habitats within western Europe.[21]

See also

References

- Oxford English Dictionary, 1971

- Monika Buchmüller-Pfaff: Namen im Grenzland - Methoden, Aspekte und Zielsetzung in der Erforschung der lothringisch-saarländischen Toponomastik, Francia 18/1 (1991), Francia-Online: Sex nstitut historique allemand de Paris - Deutsches Historisches Institut Paris: OnlineressourceArchived 2015-01-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Max Pfister: Altromanische Relikte in der östlichen und südlichen Galloromania, in den rheinischen Mundarten, im Alpenraum und in Oberitalien. In : Sieglinde Heinz, Ulrich Wandruszka [ed.]: Fakten und Theorien : Beitr. zur roman. u. allg. Sprachwiss.; Festschr. für Helmut Stimm zum 65. Geburtstag, Tübingen 1982, pp. 219 – 230, ISBN3-87808-936-8

- "Natural world: the solar system: highest cliffs". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 2006-05-21. Retrieved 2014-11-16.

- "Highest Cliffs". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 2005-11-27. Retrieved 2006-05-02.

- Lück, Michael (2008). The Encyclopedia of Tourism and Recreation in Marine Environments By Michael Lück. ISBN9781845933500 . Archived from the original on 2017-12-06. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- "Planet Fear". Archived from the original on 2012-03-26. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- "Polar Sun Spire". SummitPost.Org. Archived from the original on 2008-12-02. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- "Climbing in Tasermiut". bigwall.dk. Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- "The American Alpine Journal"(PDF) . 1986. Archived from the original(PDF) on October 28, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- The Summer 1998 Slovak Expedition to Greenland (Jamesák International)Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Jon Roberts: Agdlerussakasit (1750 m), east face, new route on east face; The Butler (900 m) and Mark (900 m), first ascents. American Alpine Journal (AAJ) 2004, pp. 266–267

- "Catalogue of place names in northern East Greenland". Geological Survey of Denmark. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- "Backpacking - Kootenay National Park". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2019-09-29. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- "Geology Fieldnotes". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2013-05-22. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- "Home - South West Coast Path". southwestcoastpath.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-11.

- [1]

- Smith, Oliver; Momber, Gary; Bates, C Richard; Garwood, Paul; Fitch, Simon; Gaffney, Vincent; Allaby, Robin G (2015). "Sedimentary DNA from a submerged site reveals wheat in the British Isles 8000 years ago". Science. academic.microsoft.com: sciencemag. 347 (6225): 998–1001. Bibcode:2015Sci...347..998S. doi:10.1126/SCIENCE.1261278. hdl:10454/9405. PMID25722413 . S2CID1167101. Retrieved 7 June 2021 – via Microsoft Academic.

- Mount Wilson 1:25000 Map. NSW Govt. May 2014.

- C.Michael Hogan. 2010. Abiotic factor. Encyclopedia of Earth. eds Emily Monosson and C. Cleveland. National Council for Science and the EnvironmentArchived June 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Washington DC

- González, García; Begoña, María; Espadaler, X; Olesen, Jens M (12 September 2012). Bente Jessen Graae (ed.). "Extreme Reproduction and Survival of a True Cliffhanger: The Endangered Plant Borderea chouardii (Dioscoreaceae)". PLOS ONE. digital.csic.es: Public Library of Science. 7 (9): e44657. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...744657G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044657. PMC3440335 . PMID22984539. Retrieved 7 June 2021 – via CORE.

External links

- "Cliff" . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.